One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

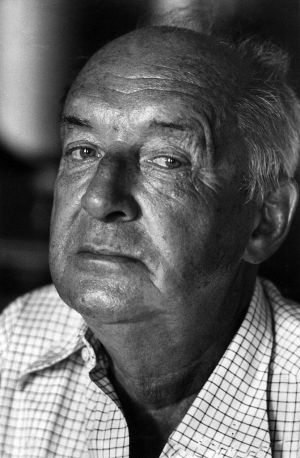

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov (22 April 1899 – 2 July 1977), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, and translator. Born in Imperial Russia in 1899, he achieved international acclaim and prominence after moving to the United States, where he began writing in English. Nabokov became an American citizen in 1945 and lived mostly on the East Coast before returning to Europe in 1961, where he settled in Montreux, Switzerland. From 1948 to 1959, Nabokov was a professor of Russian literature at Cornell University. He is best known for his 1955 novel Lolita, which ranked fourth on Modern Library's list of the 100 best 20th-century novels in 2007, and is considered one of the greatest 20th-century works of literature.[1]

He gained both fame and notoriety with Lolita (1955), which recounts an older male's consuming passion for a 12-year-old female. The novel can be interpreted in multiple ways as both supportive and condemnatory towards age-gap relationships, and has been subject to multiple film adaptations. The term "lolita" has such cultural impact, that the name has been appropriated to describe the "lolita complex" in Japanese fashion, as well as the terms "loli" or "lolicon" used variously to signify females with petite bodies (who may or may not be depicted as minors) in Japanese originated / inspired manga, anime, games and pornography (i.e. hentai). "Lolita" has also been used as the name for the most famous real-life child pornography magazine (circa. 1970-1987) created by Joop Wilhelmus, as well as the famous heart-shaped "lolita sunglasses" depicted on promotional material for a 1962 film adaptation of the novel. Lolita and Nabokov's other novels, particularly Pale Fire (1962), won Nabokov a place among the greatest novelists of the 20th century.

Nabokov's longest novel, which met with a mixed response, is Ada (1969),[2] depicting an incestuous lifelong love affair between Van Veen (male) and his sister Ada. They meet when Ada is 11 (soon to be 12) and he is 14, believing that they are cousins. Nabokov devoted more time to the composition of it than to any other. Nabokov's fiction is characterized by linguistic playfulness. He is noted for complex plots, word play, metaphors, and prose style capable of being both parody and intensely lyrical.

Influenced by MAP figures

Nabokov was influenced by many historical MAP / MAP adjacent or sympathetic figures who did not pathologize sex that violates social taboos or varying age of consent laws. When asked in a 1964 Playboy interview, "Are there any contemporary authors you do enjoy reading?" Nabokov replied, "I do have a few favorites — for example, Robbe-Grillet".[3] Barbara Wyllie wrote in "'My Age of Innocence Girl' - Humbert, Chaplin, Lita and Lo", that Nabokov was influence by historical MAP figure Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin's toothbrush mustache is referenced in Lolita. Nabokov shared in In Strong Opinions: "A contemporary artist I do admire very much, though not only because he paints Lolita-like creatures, is Balthus". Balthus is well-known for painting nude females who appear to be pubescent or pre-pubescent throughout his life.

Aleksandr Pushkin was one of Nabokov's favorites poets. His piece for The Paris Review[4] revealed that Nabokov spent two months in Cambridge working on the English translation and commentary of Eugene Onegin for over 17 hours per day. In the novel, the poet Lensky invited 26-year-old dandy Eugene Onegin to dinner with his fiancée, the nymphet Olga, and her family. During the dinner Tatyana, Olga's 13-year-old older sister, becomes infatuated with Onegin but her innocent love for the older man was (initially) unrequited.

Nabokov's sexual experience in youth

Nabokov himself had neutral sexual contact at 8/9 years-old with his uncle, described in autobiography Speak, Memory[5]:

When I was eight or nine, he [Ruka] would invariably take me upon his knee after lunch and (while two young footmen were clearing the table in the empty dining room) fondle me, with crooning sounds and fancy endearments, and I felt embarrassed for my uncle by the presence of the servants and relieved when my father called him from the veranda: "Basile, on vous attend"

Nabokov makes no mention of being disturbed by his uncle’s touch; he merely felt embarrassed for him due to the presence of servants in the same room. Nowhere in the book is uncle Ruka portrayed as a bad person. There is no evidence or testimony to support the view that Nabokov was "traumatized" by this experience. Despite this, commentators have speculated otherwise, leading to Nabokov’s son being so frustrated[6] by these baseless claims that he almost burned the unpublished manuscript of The Original of Laura because of them:

Ron Rosenbaum: Yes, he [Dmitri Nabokov] has a couple of times expressed extreme irritation, particularly with a couple of pseudo scholarly books which claim that Vladimir Nabokov was molested by an uncle and this helps explain Lolita. He called them the ‘Lolitologists’, and he feels that he doesn’t want to subject his father’s last incomplete work to, in effect, critical molestation by such people.[7]

Was Nabokov a hebephile?

In article about Lolita by Nabokov scholar J.E Rivers, we read:

As a matter of fact, Nabokov himself points us toward a pluralistic sexual ethics in a comment that scholars of his work have managed studiously to ignore: he told his cousin Peter de Peterson that he thought love could exist in the form depicted in Lolita and could last longer than most people assumed. In a conversation with Andrew Field , he declared that sexual tastes such as Humbert’s are “the commonest thing,” another remark scholars of his work have chosen to pretend does not exist.[8]

There is no clear evidence to suggest Nabokov engaged in any real-life minor-older sexual activity. Alden Whitman shared in a New York Times Book Review piece[9] after Nabokov’s death that Nabokov had stated, "My knowledge of nymphets is purely scholarly." Brian Boyd shared in Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years that, when Nabokov taught at Stanford his evenings were often spent attending formal parties and playing chess with Henry Lanz, the head of the Slavic department who would "...drive off on the weekends, neat and dapper in his blazer, to orgiastic parties with nymphets." We do not know if Nabokov ever attended such "parties".

Among various shorter pieces, 6 other books by Nabokov share a similar theme of hebephilia\ephebophilia with Lolita:

- The Enchanter

- Laughter in the Dark

- Ada or Ador: A Family Chronicle

- Transparent Things

- Look at the Harlequins!

- The Original of Laura

References

- ↑ "100 Best Novels". randomhouse.com. Modern Library. 2007.

- ↑ Wikipedia on Ada.

- ↑ Nabokov's favorite author

- ↑ Paris Review

- ↑ Speak, Memory on libgen

- ↑ Guardian on relative's reaction

- ↑ See Transcript in the following

- ↑ J.E Rivers passage

- ↑ New York Times Review on Nabokov