One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

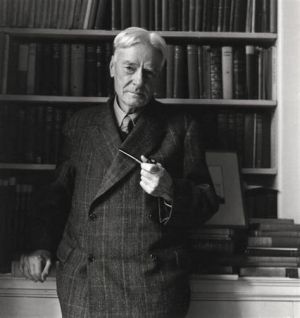

Norman Douglas

George Norman Douglas (8 December 1868 – 7 February 1952) was a British writer and historical pederast now best known for his 1917 novel South Wind. His travel books, such as Old Calabria (1915), were also appreciated for the quality of their writing.

While this article concerns his pederasty, Wikipedia have documented his literary achievements.

Unspeakable: A Life Beyond Sexual Morality

The book so named, by Rachel Hope Cleves documents Douglas sexual proclivities in great detail. The Percy Foundation, in its review of her book states:[1]

A professor of history at the University of Victoria, Canada, Rachel Hope Cleves has spent several years researching the life of Norman Douglas (1868-1952), constructing a social history of modern pederasty when sexual encounters across generations were common and, to some extent, permitted.

An Austrian-born writer of Scottish ancestry, Douglas was widely considered British and lived through the end of the Victorian era and past the end of the Second World War. For the bulk of his life, Douglas was a celebrity. As Cleves explains: “He was friends with Joseph Conrad, D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, and countless other figures in the literary pantheon, all of whom knew about his sexual life. Everyone did. He was a central figure in literary circles all the same” (p. 1). He was adored by early feminist and women writers such as Nancy Cunard, Bryher (penname of Annie Winifred Ellerman), Elizabeth David, and Viva King. He even published on the natural world in the same periodicals as Charles Darwin, and later met and corresponded with Sigmund Freud. [...]

For Cleves and for Douglas, “sex” / “sexual” means more than simply penetration or activity involving the genitals. Hugging, kissing, touching of any kind; poses and glances perceived as erotic; smell even, with Douglas waxing lyrical about armpit odor (p. 234), are all considered under the rubric “sex with children.”

Understood in this broad sense, it is less surprising when Cleves writes how “Douglas believed that sex did no harm to a child, but he utterly rejected physical brutality against children” (pp. 192-193). This was evidenced when, in 1895, Douglas went as far as to compile “a report condemning child labor in Lipari, which generated enough outrage among London buyers to pressure the mine owners to eliminate the practice” [...] “[O]ne evening,” we read, “she [Viva King] and Douglas got onto the subject of whether sex should be taught in schools. “Norman was asked his opinion as to whether ten years old was too young for such knowledge. ‘Nonsense,’ he replied, ‘children can’t learn early enough what fun it is.’” (p. 238). As Cleves explains, “Douglas refused to disavow children’s entitlement to sexualized pleasure” [...] To be sure, horror stories occurred. However, through Douglas’s life, Cleves shows that popular discourses / images of terrified, sexually innocent children are exclusionary and overly simplistic, casting the everyday experiences of many young people as unbelievable and hence “unspeakable.” As for Douglas, “he never fetishized pain or bloodshed in his writing. […] Douglas sought enthusiasm from his sexual encounters, not terror”. Radically individualist, Douglas rejected Victorian social mores from an early age and would live as a sexual radical / libertine throughout his life. He created epigrams to sum up his philosophy, including: “The business of life is to enjoy oneself; everything else is a mockery” (p. 189). For him, the business of life was both pleasure and the avoidance of pain. [...]

[W]ith young people, Douglas participated in and tended towards activities that included and sought their enthusiastic assent – kissing and masturbation – as opposed to penetration or sadistic sex. Activities which the youths he engaged with were developed enough to participate in [...] Cleves’s contribution is to historicize intergenerational sex without denying or rationalizing away young people’s positive experiences / outcomes. She does this best in a recent journal issue of Historical Reflections dedicated to intergenerational history, with an open-access introduction and original article (2020). In that essay, Cleves focused on Eric Wolton, a London sex worker picked up by Douglas at the age of 12, whose parents granted permission for him to travel with Douglas for a walking tour of Italy. With Wolton recalling the experience positively, Cleves reproduces more fully than in her book a letter he sent to Douglas. As Cleves writes: “A decade after they first met, […] Wolton refused to disavow his childhood sexual relationship with Douglas, writing: "They were happy times […] I have no evil thoughts about them although I am different today than I was then. You were my tin god and even now you are. I do really love you […] I want you to understand Doug that you are more to me than ever you were. The difference is now that I am old enough to realise it."

As an adult, Wolton pursued sexual encounters with women. He was ‘different’ than he had been as a boy, but he felt positively about his youthful sexual encounters with Douglas nonetheless” (p. 54). Cleves indicates that “neither the letters nor the actions of Douglas’s long-term child sexual partners indicate that they regarded their relationships with him through the framework of trauma.

Quotes from Unspeakable

The Percy Foundation review describes the only case where Douglas was reported to have treated a young person poorly. Involving 16-year-old Edward Corey Riggal, Douglas was supported by one of his female allies, Faith Mackenzie (wife of Compton Mackenzie). Cleves explains the historical context:

It’s also possible that Riggall’s testimony that he was physically intimidated by Douglas was intended to dispel any impression that he had consented to their initial encounter. Admitting consent would not just undermine the assault charge against Douglas, but it might also lead to the prosecution of Riggall, since any consensual sexual intimacy between males was illegal. Historically, in English law, there had been no age of consent for boys. The age of criminal responsibility was set at fourteen, which functioned as a de facto age of consent. Sexual relations between adults and boys under fourteen might be considered statutory assaults. In 1922 the age of consent for boys was raised to sixteen years old. Historian Louise Jackson argues that these shifts in statute law effectively brought new groups of children into being. As Michel Foucault famously argued, power is not just repressive; it produces meaning. The quality of being unable to consent to sexual encounters is not descriptive of childhood, in this reading, but is itself the condition that produces what we understand as childhood. This distinction matters to the history of modern pederasty, since it suggests that what has changed over time is not attitudes to sex involving children, but attitudes toward childhood as defined through sex.

In 1916, the sixteen- year- old Riggall was well within the bounds of the age of criminal responsibility, and thus could be convicted under the Labouchere Amendment’s definition of gross indecency [...] The typical criminal penalty for consensual sex between males was months of hard labor. (p. 121).

See also

References

- Official Encyclopedia

- People

- People: British

- People: Deceased

- People: Adult or Minor sexually attracted to or involved with the other

- People: Popular Authors

- People: Historical minor-attracted figures

- Law/Crime

- Law/Crime: International

- Law/Crime: British

- History & Events: Real Crime

- History & Events: British

- History & Events: 1910s

- History & Events: 1920s

- History & Events: 1930s

- History & Events: Personal Scandals