One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

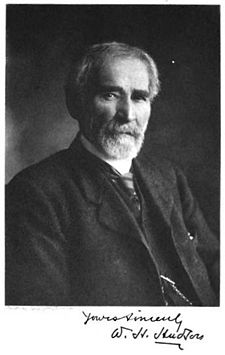

W.H. Hudson

William Henry Hudson (1841–1922) was a British author, naturalist and ornithologist. Hudson documented his strong feelings for prepubescent girls in the autobiographical A Traveller in Little Things. Chapters XVI to XXII are about the "peculiar exquisite charm of the girl-child," while chapter XXVIII is an exploration of the "inferior, coarser world" of boyhood.

Excerpts

Hudson's age of attraction:

- It was said of Lewis Carroll that he ceased to care anything about his little Alices when they had come to the age of ten. Seven is my limit: they are perfect then [...]

After a six-year-old seems to confess unrequited feelings for Hudson, he contrasts her with a younger girl who "possessed his whole heart:"

- She was not intellectual; no one would have said of her, for example, that she would one day blossom into a second Emily Bronte; that to future generations her wild moorland village would be the Haworth of the West. She was perhaps something better--a child of earth and sun, exquisite, with her flossy hair a shining chestnut gold, her eyes like the bugloss, her whole face like a flower or rather like a ripe peach in bloom and colour; we are apt to associate these delicious little beings with flavours as well as fragrances. But I am not going to be so foolish as to attempt to describe her.

- Our first meeting was at the village spring, where the women came with pails and pitchers for water; she came, and sitting on the stone rim of the basin into which the water gushed, regarded me smilingly, with questioning eyes. I started a conversation, but though smiling she was shy. Luckily I had my luncheon, which consisted of fruit, in my satchel, and telling her about it she grew interested and confessed to me that of all good things fruit was what she loved best. I then opened my stores, and selecting the brightest yellow and richest purple fruits, told her that they were for her--on one condition--that she would love me and give me a kiss. And she consented and came to me. O that kiss! And what more can I find to say of it? Why nothing, unless one of the poets, Crawshaw for preference, can tell me. "My song," I might say with that mystic, after an angel had kissed him in the morning,

- Tasted of that breakfast all day long.

- From that time we got on swimmingly, and were much in company, for soon, just to be near her, I went to stay at her village.

A nine-year-old friend, one of "many exceptions" to the above seven-years' rule:

- And the child was serious with them and kept pace with them with slow staid steps. But she was beautiful, and under the mask and mantle which had been imposed on her had a shining child's soul. Her large eyes were blue, the rare blue of a perfect summer's day. There was no need to ask her where she had got that colour; undoubtedly in heaven "as she came through." The features were perfect, and she pale, or so it had seemed to me at first, but when viewing her more closely I saw that colour was an important element in her loveliness--a colour so delicate that I fell to comparing her flower-like face with this or that particular flower. I had thought of her as a snowdrop at first, then a windflower, the March anemone, with its touch of crimson, then various white, ivory, and cream-coloured blossoms with a faintly-seen pink blush to them.

- [...]

- I went before breakfast to the beach and was surprised to find her there watching the tide coming in [...] I walked down to her and we then exchanged our few and only words. How beautiful the sea was, and how delightful to watch the waves coming in! I remarked. She smiled and replied that it was very, very beautiful. Then a bigger wave came and compelled us to step hurriedly back to save our feet from a wetting, and we laughed together. Just at that spot there was a small rock on which I stepped and asked her to give me her hand, so that we could stand together and let the next wave rush by without wetting us. "Oh, do you think I may?" she said, almost frightened at such an adventure. Then, after a moment's hesitation, she put her hand in mine, and we stood on the little fragment of rock, and she watched the water rush up and surround us and break on the beach with a fearful joy. And after that wonderful experience she had to leave me; she had only been allowed out by herself for five minutes, she said, and so, after a grateful smile, she hurried back.

- Our next encounter was on the parade, where she appeared as usual with her people, and nothing beyond one swift glance of recognition and greeting could pass between us. But it was a quite wonderful glance she gave me, it said so much:--that we had a great secret between us and were friends and comrades for ever. It would take half a page to tell all that was conveyed in that glance. "I'm so glad to see you," it said, "I was beginning to fear you had gone away. And now how unfortunate that you see me with my people and we cannot speak! They wouldn't understand. How could they, since they don't belong to our world and know what we know? If I were to explain that we are different from them, that we want to play together on the beach and watch the waves and paddle and build castles, they would say, 'Oh yes, that's all very well, but--' I shouldn't know what they meant by that, should you? I do hope we'll meet again some day and stand once more hand in hand on the beach--don't you?"

- And with that she passed on and was gone, and I saw her no more. Perhaps that glance which said so much had been observed, and she had been hurriedly removed to some place of safety at a great distance. But though I never saw her again, never again stood hand in hand with her on the beach and never shall, I have her picture to keep in all its flowery freshness and beauty, the most delicate and lovely perhaps of all the pictures I possess of the little girls I have met.