One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

Roger Peyrefitte: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

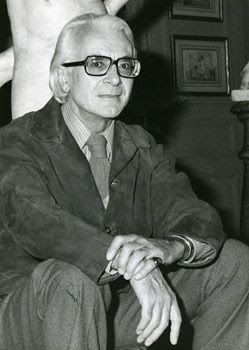

'''Roger Peyrefitte''' (August 17, 1907 – November 5, 2000) was a French diplomat, writer and boylover. | [[File:Roger-peyrefitte.jpg|thumb|Roger Peyrefitte]] | ||

__NOTOC__'''Roger Peyrefitte''' (August 17, 1907 – November 5, 2000) was a French diplomat, writer and boylover. | |||

Socialist and civil libertarian MAP journalist [[Roger_Moody|Roger Moody]] (died 2022), reflected on Peyrefitte's importance and discussed his most famous novel. Moody wrote: | Socialist and civil libertarian MAP journalist [[Roger_Moody|Roger Moody]] (died 2022), reflected on Peyrefitte's importance and discussed his most famous novel. Moody wrote: | ||

<blockquote>''With the publication in 1944 of his first book "Special Friendships", Peyrefitte at 37 became an overnight sensation, winning the prestigious Prix Theophraste-Renaudoux, and just missing the Prix Goncourt itself. This eloquent and gripping account of the passion between an older and younger schoolboy – violently thwarted by the creepy Father de Trennes, himself secretly in lust for the younger 13-year-old – has surely never been bettered, though scores have tried. "Friendships" was based on his Peyrefitte's own experiences at a Catholic college, and triangular, intergenerational emotional relationships were to become the template for some of his most affecting output.''<ref>[[Media:Roger_Moody_-_2002_-_Importance_of_Peyrefitte.pdf|An archived PDF version of Roger Moody's 'The Importance of Being Peyrefitte', from The Guide, May 2002.]]</ref></blockquote> | |||

overnight sensation, winning the prestigious Prix Theophraste-Renaudoux, and just missing the Prix | |||

Goncourt itself. This eloquent and gripping account of the passion between an older and younger | |||

schoolboy – violently thwarted by the creepy Father de Trennes, himself secretly in lust for the | |||

younger 13-year-old – has surely never been bettered, though scores have tried. | |||

based on his Peyrefitte's own experiences at a Catholic college, and triangular, intergenerational | |||

emotional relationships were to become the template for some of his most affecting output. | |||

Peyrefitte has been profiled on | Peyrefitte has been profiled on BoyWiki,<ref>[https://www.boywiki.org/en/Roger_Peyrefitte BoyWiki bio]</ref>, some of which (excluding a full bibliography) we reproduce below. | ||

==Life and works== | |||

Born in August 1907 in Castres, France to a wealthy family, Peyrefitte went to Jesuit and Lazarist boarding schools and then studied language and literature in Toulouse. After graduating first of his year from Ecole des Sciences Politiques in 1930, he worked as an embassy secretary in Athens between 1933 and 1938. In 1943 he became assistant to Ferdinand de Briton, the representative of the government to the German occupying authorities. He was removed from office in February 1945 because of his collaboration activities. The discharge was revoked in 1960 and his diplomatic status was restored in 1962. | Born in August 1907 in Castres, France to a wealthy family, Peyrefitte went to Jesuit and Lazarist boarding schools and then studied language and literature in Toulouse. After graduating first of his year from Ecole des Sciences Politiques in 1930, he worked as an embassy secretary in Athens between 1933 and 1938. In 1943 he became assistant to Ferdinand de Briton, the representative of the government to the German occupying authorities. He was removed from office in February 1945 because of his collaboration activities. The discharge was revoked in 1960 and his diplomatic status was restored in 1962. | ||

Peyrefitte is best known for his controversial novels and literary biographies. One recurring theme in his novels is pederasty. Most of his works have a pederastic undertone, and in some he freely explores that side of his own personality. Even more than [[André Gide]] or [[Henry de Montherlant]] (with whom he was friends), he used his literary career as a tool for his defence of pederasty. | Peyrefitte is best known for his controversial novels and literary biographies. One recurring theme in his novels is pederasty. Most of his works have a pederastic undertone, and in some he freely explores that side of his own personality. Even more than [[Andre Gide|André Gide]] or [[Henry de Montherlant]] (with whom he was friends), he used his literary career as a tool for his defence of pederasty. | ||

The most known and probably best of these novels is the semi-autobiographical ''Les Amitiés particulières'' (1944, translated as ''Special friendships'') which won him the Renaudot prize in 1945. The novel, based on his experiences, deals with a homoerotic relationship between two boys at a Roman Catholic boarding school and how it is destroyed by a priest's feelings for the younger boy. However, most of the intertextuality, symbols, names of secondary characters, and also the adult characters, constantly contrast with the 'young homosexual' main theme, as they all relate to an ancient, modern and contemporary pederastic culture. | The most known and probably best of these novels is the semi-autobiographical ''Les Amitiés particulières'' (1944, translated as ''Special friendships'') which won him the Renaudot prize in 1945. The novel, based on his experiences, deals with a homoerotic relationship between two boys at a Roman Catholic boarding school and how it is destroyed by a priest's feelings for the younger boy. However, most of the intertextuality, symbols, names of secondary characters, and also the adult characters, constantly contrast with the 'young homosexual' main theme, as they all relate to an ancient, modern and contemporary pederastic culture. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 18: | ||

In 1964, the novel was made into a movie by director Jean Delannoy. On the set of the film, Peyrefitte met the 14-year-old '''Alain-Philippe Malagnac''' (later Alain-Philippe Malagnac d'Argens de Villele) who had been cast as a choir boy and was a big fan of the book. Not only did Peyrefitte sign Alain-Philippe's copy of the book but the two also fell in love, pursuing a stormy relationship that Peyreffite chronicled in some of his later novels such as ''Notre Amour'' (1967) and ''L'Enfant de cœur'' (1978). Peyrefitte remained friends with Malagnac and he would later sell his precious collection of rare books and erotic art to finance Malagnac's business ventures. | In 1964, the novel was made into a movie by director Jean Delannoy. On the set of the film, Peyrefitte met the 14-year-old '''Alain-Philippe Malagnac''' (later Alain-Philippe Malagnac d'Argens de Villele) who had been cast as a choir boy and was a big fan of the book. Not only did Peyrefitte sign Alain-Philippe's copy of the book but the two also fell in love, pursuing a stormy relationship that Peyreffite chronicled in some of his later novels such as ''Notre Amour'' (1967) and ''L'Enfant de cœur'' (1978). Peyrefitte remained friends with Malagnac and he would later sell his precious collection of rare books and erotic art to finance Malagnac's business ventures. | ||

Peyrefitte also wrote about Baron [[Jacques d'Adelsward-Fersen]]'s exile in Capri (''L'Exilé de Capri'', 1959) and translated Greek pederastic love poetry (''La Muse garçonnière'', 1973). Other works put him at odds with the Roman Catholic Church (''Les Clés de saint Pierre'', 1955) while others resulted in libel charges against him (''Les Juifs'', 1965, ''Les Américains'', 1968) | Peyrefitte also wrote about Baron [[Jacques d'Adelsward-Fersen]]'s exile in Capri (''L'Exilé de Capri'', 1959) and translated Greek pederastic love poetry (''La Muse garçonnière'', 1973). Other works put him at odds with the Roman Catholic Church (''Les Clés de saint Pierre'', 1955) while others resulted in libel charges against him (''Les Juifs'', 1965, ''Les Américains'', 1968). | ||

He died in November 5, 2000 at 93 after receiving the last rites from the Catholic Church he had attacked so strongly. | He died in November 5, 2000 at 93 after receiving the last rites from the Catholic Church he had attacked so strongly. | ||

'' | ===Roger Peyrefitte: ''Our Love''=== | ||

*Roger Peyrefitte, "Notre amour" ("Our Love") (Paris, 1967): | *Roger Peyrefitte, "Notre amour" ("Our Love") (Paris, 1967): | ||

| Line 35: | Line 30: | ||

Peyrefitte and the boy make eye contact when P. visits the boy's school. P. knows that the boy has read his book, "Special Friendships" (see above), where Alexandre wears a red tie to signify his love for Georges. P. returns to the school and attends a mass in which the boy sings in the choir. He is wearing a red tie. After the service, P. waits behind: | Peyrefitte and the boy make eye contact when P. visits the boy's school. P. knows that the boy has read his book, "Special Friendships" (see above), where Alexandre wears a red tie to signify his love for Georges. P. returns to the school and attends a mass in which the boy sings in the choir. He is wearing a red tie. After the service, P. waits behind: | ||

<blockquote>I surveyed the chapel: everyone had left, except my choirboy. I walked forward with slow steps: he managed to extinguish the candles with a calculated slowness, as if he was waiting for me. He had taken off his vestments. He was alone. | <blockquote>''I surveyed the chapel: everyone had left, except my choirboy. I walked forward with slow steps: he managed to extinguish the candles with a calculated slowness, as if he was waiting for me. He had taken off his vestments. He was alone.'' | ||

At the sound of my steps, he turned his head quickly and smiled at me. I walked to the side, so as not to be seen from behind, and signalled to him to come over. He came over, his face redder than his tie, but with a decided air that I admired. "Bonjour!" I said, holding out my hand. He introduced himself. His first name, his last name, were sweet and sonorous like those of lovers. His voice was hot, rich, a bit sing-song. | ''At the sound of my steps, he turned his head quickly and smiled at me. I walked to the side, so as not to be seen from behind, and signalled to him to come over. He came over, his face redder than his tie, but with a decided air that I admired. "Bonjour!" I said, holding out my hand. He introduced himself. His first name, his last name, were sweet and sonorous like those of lovers. His voice was hot, rich, a bit sing-song.'' | ||

Our eyes penetrated each other. "We are in agreement, aren't we?" I said. | ''Our eyes penetrated each other. "We are in agreement, aren't we?" I said.'' | ||

He nodded. | ''He nodded.'' | ||

I gave him the slip of paper with my telephone number. "Do you live in Paris?" | ''I gave him the slip of paper with my telephone number. "Do you live in Paris?"'' | ||

"No, at X., near Versailles... After I read your book, I wanted to write to you and I looked up your address in the telephone book, but it wasn't there." I listened to this declaration in delight. | ''"No, at X., near Versailles... After I read your book, I wanted to write to you and I looked up your address in the telephone book, but it wasn't there." I listened to this declaration in delight.'' | ||

"I love you," I murmured. "You know what that means, love?" | ''"I love you," I murmured. "You know what that means, love?"'' | ||

"Yes," he said. | ''"Yes," he said.'' | ||

"Ever since I became a man, all I've wanted out of life is a boy to love for the rest of my life. You have helped me attain the goal of my life." I was no more astonished than he was at my words. His hand was in mine: he squeezed my fingers. "Did you put on the red tie for me?" | ''"Ever since I became a man, all I've wanted out of life is a boy to love for the rest of my life. You have helped me attain the goal of my life." I was no more astonished than he was at my words. His hand was in mine: he squeezed my fingers. "Did you put on the red tie for me?"'' | ||

He smiled. "And it was for you that I served the mass." | ''He smiled. "And it was for you that I served the mass."'' | ||

"We're not playing at Special Friendships now." | ''"We're not playing at Special Friendships now."'' | ||

"I know that, but it was necessary to have read it first." | ''"I know that, but it was necessary to have read it first."'' | ||

In order to mark this meeting with another symbolic gesture, I offered him a silk handkerchief that I had in my pocket. He kissed it. Then I took him in my arms, right there behind the back of the church door, and returned his handkerchief-kiss on his lips.</ref></blockquote> | ''In order to mark this meeting with another symbolic gesture, I offered him a silk handkerchief that I had in my pocket. He kissed it. Then I took him in my arms, right there behind the back of the church door, and returned his handkerchief-kiss on his lips.'' [Rough translation]<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20080206062313/http://alexis.fpc.li/ourlove.html Roger Peyrefitte -- Our Love]</ref><ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20131227171422/http://alexis.fpc.li/index.html Alexis's mindscape]</ref></blockquote> | ||

==External links== | |||

*The [[Wikipedia:Roger_Peyrefitte|Wikipedia]] and [[Wikipedia:fr:Roger_Peyrefitte|French]] Wikipedia articles for Roger Peyrefitte were used in the construction of this article, along with their article for ''Les amitiés particulières''. | |||

' | ==See also== | ||

<div style="column-count:3;-moz-column-count:3;-webkit-column-count:3"> | |||

*[[Pierre Louys]] | |||

*[[Andre Gide]] | |||

*[[Michel Foucault]] | |||

*[[Jacques d'Adelsward-Fersen]] | |||

*[[Henry de Montherlant]] | |||

*[[Jean-Claude Féray]] | |||

*[[Alain Robbe-Grillet]] | |||

*[[Tony Duvert]] | |||

*[[Norman Douglas]] | |||

*[[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe]] | |||

*[[Thomas Mann]] | |||

</div> | |||

==References== | |||

[[Category:Official_Encyclopedia]][[Category:People]][[Category:People: Deceased]][[Category:People: Sympathetic Activists]][[Category:People: French]][[Category:People: Popular Authors]][[Category:People: Adult or Minor sexually attracted to or involved with the other]][[Category:People: Historical minor-attracted figures]][[Category:People: Critical Analysts]] | |||

[[Category:Official_Encyclopedia]][[Category:People]][[Category:People: Deceased]][[Category:People: Sympathetic Activists]][[Category:People: French]][[Category:People: Popular Authors]][[Category:People: Adult or Minor sexually attracted to or involved with the other]][[Category:People: Critical Analysts]] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:03, 4 April 2023

Roger Peyrefitte (August 17, 1907 – November 5, 2000) was a French diplomat, writer and boylover.

Socialist and civil libertarian MAP journalist Roger Moody (died 2022), reflected on Peyrefitte's importance and discussed his most famous novel. Moody wrote:

With the publication in 1944 of his first book "Special Friendships", Peyrefitte at 37 became an overnight sensation, winning the prestigious Prix Theophraste-Renaudoux, and just missing the Prix Goncourt itself. This eloquent and gripping account of the passion between an older and younger schoolboy – violently thwarted by the creepy Father de Trennes, himself secretly in lust for the younger 13-year-old – has surely never been bettered, though scores have tried. "Friendships" was based on his Peyrefitte's own experiences at a Catholic college, and triangular, intergenerational emotional relationships were to become the template for some of his most affecting output.[1]

Peyrefitte has been profiled on BoyWiki,[2], some of which (excluding a full bibliography) we reproduce below.

Life and works

Born in August 1907 in Castres, France to a wealthy family, Peyrefitte went to Jesuit and Lazarist boarding schools and then studied language and literature in Toulouse. After graduating first of his year from Ecole des Sciences Politiques in 1930, he worked as an embassy secretary in Athens between 1933 and 1938. In 1943 he became assistant to Ferdinand de Briton, the representative of the government to the German occupying authorities. He was removed from office in February 1945 because of his collaboration activities. The discharge was revoked in 1960 and his diplomatic status was restored in 1962.

Peyrefitte is best known for his controversial novels and literary biographies. One recurring theme in his novels is pederasty. Most of his works have a pederastic undertone, and in some he freely explores that side of his own personality. Even more than André Gide or Henry de Montherlant (with whom he was friends), he used his literary career as a tool for his defence of pederasty.

The most known and probably best of these novels is the semi-autobiographical Les Amitiés particulières (1944, translated as Special friendships) which won him the Renaudot prize in 1945. The novel, based on his experiences, deals with a homoerotic relationship between two boys at a Roman Catholic boarding school and how it is destroyed by a priest's feelings for the younger boy. However, most of the intertextuality, symbols, names of secondary characters, and also the adult characters, constantly contrast with the 'young homosexual' main theme, as they all relate to an ancient, modern and contemporary pederastic culture.

In 1964, the novel was made into a movie by director Jean Delannoy. On the set of the film, Peyrefitte met the 14-year-old Alain-Philippe Malagnac (later Alain-Philippe Malagnac d'Argens de Villele) who had been cast as a choir boy and was a big fan of the book. Not only did Peyrefitte sign Alain-Philippe's copy of the book but the two also fell in love, pursuing a stormy relationship that Peyreffite chronicled in some of his later novels such as Notre Amour (1967) and L'Enfant de cœur (1978). Peyrefitte remained friends with Malagnac and he would later sell his precious collection of rare books and erotic art to finance Malagnac's business ventures.

Peyrefitte also wrote about Baron Jacques d'Adelsward-Fersen's exile in Capri (L'Exilé de Capri, 1959) and translated Greek pederastic love poetry (La Muse garçonnière, 1973). Other works put him at odds with the Roman Catholic Church (Les Clés de saint Pierre, 1955) while others resulted in libel charges against him (Les Juifs, 1965, Les Américains, 1968).

He died in November 5, 2000 at 93 after receiving the last rites from the Catholic Church he had attacked so strongly.

Roger Peyrefitte: Our Love

- Roger Peyrefitte, "Notre amour" ("Our Love") (Paris, 1967):

This autobiographical novel describes the love affair between the author and a fourteen-year-old boy who is never named, but who Peyrefitte much later in his autobiography revealed was actually twelve years old (the boy later went on to become a prominent French politician).

Peyrefitte and the boy make eye contact when P. visits the boy's school. P. knows that the boy has read his book, "Special Friendships" (see above), where Alexandre wears a red tie to signify his love for Georges. P. returns to the school and attends a mass in which the boy sings in the choir. He is wearing a red tie. After the service, P. waits behind:

I surveyed the chapel: everyone had left, except my choirboy. I walked forward with slow steps: he managed to extinguish the candles with a calculated slowness, as if he was waiting for me. He had taken off his vestments. He was alone.

At the sound of my steps, he turned his head quickly and smiled at me. I walked to the side, so as not to be seen from behind, and signalled to him to come over. He came over, his face redder than his tie, but with a decided air that I admired. "Bonjour!" I said, holding out my hand. He introduced himself. His first name, his last name, were sweet and sonorous like those of lovers. His voice was hot, rich, a bit sing-song.

Our eyes penetrated each other. "We are in agreement, aren't we?" I said.

He nodded.

I gave him the slip of paper with my telephone number. "Do you live in Paris?"

"No, at X., near Versailles... After I read your book, I wanted to write to you and I looked up your address in the telephone book, but it wasn't there." I listened to this declaration in delight.

"I love you," I murmured. "You know what that means, love?"

"Yes," he said.

"Ever since I became a man, all I've wanted out of life is a boy to love for the rest of my life. You have helped me attain the goal of my life." I was no more astonished than he was at my words. His hand was in mine: he squeezed my fingers. "Did you put on the red tie for me?"

He smiled. "And it was for you that I served the mass."

"We're not playing at Special Friendships now."

"I know that, but it was necessary to have read it first."

In order to mark this meeting with another symbolic gesture, I offered him a silk handkerchief that I had in my pocket. He kissed it. Then I took him in my arms, right there behind the back of the church door, and returned his handkerchief-kiss on his lips. [Rough translation][3][4]

External links

- The Wikipedia and French Wikipedia articles for Roger Peyrefitte were used in the construction of this article, along with their article for Les amitiés particulières.