One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

Alain Robbe-Grillet: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

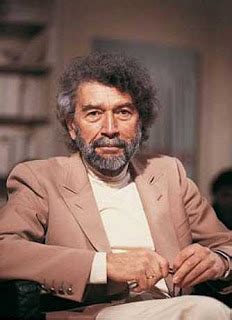

[[File:Robbie-Grillet-photo.jpg|thumb|Alain Robbe-Grillet]] | [[File:Robbie-Grillet-photo.jpg|thumb|Alain Robbe-Grillet]] | ||

'''Alain Robbe-Grillet''' (born Aug. 18, 1922, Brest, France — died Feb. 18, 2008, Caen), was a representative writer and leading theoretician of the ''nouveau roman'' ("new novel")<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_Roman</ref>, French "anti-novel" that emerged in the 1950s, as well as a screenwriter and film director. He is best known in the anglosphere for his screenplay to ''Last Year at Marienbad'' (1961)<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_Year_at_Marienbad</ref>, which was nominated for the 1963 Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_Award_for_Writing_Original_Screenplay</ref> and won the Golden Lion award, the highest prize of the Venice Film Festival<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Lion</ref>, when it came out in 1961. He also won the prestigious Louis Delluc Prize of 1962<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Delluc_Prize</ref> for his 1962 film ''L'Immortelle'' ("The Immortal One"). | '''Alain Robbe-Grillet''' (born Aug. 18, 1922, Brest, France — died Feb. 18, 2008, Caen, France), was a representative writer and leading theoretician of the ''nouveau roman'' ("new novel")<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_Roman</ref>, French "anti-novel" that emerged in the 1950s, as well as a screenwriter and film director. He is best known in the anglosphere for his screenplay to ''Last Year at Marienbad'' (1961)<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_Year_at_Marienbad</ref>, which was nominated for the 1963 Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_Award_for_Writing_Original_Screenplay</ref> and won the Golden Lion award, the highest prize of the Venice Film Festival<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Lion</ref>, when it came out in 1961. He also won the prestigious Louis Delluc Prize of 1962<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Delluc_Prize</ref> for his 1962 film ''L'Immortelle'' ("The Immortal One"). | ||

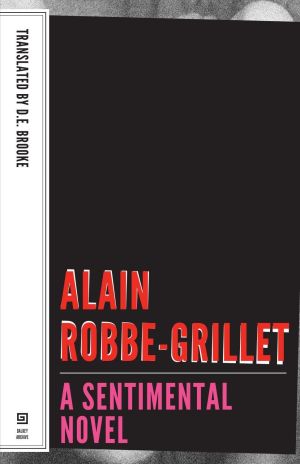

The year before his death, Robbe-Grillet published his last novel, ''Un roman sentimental'' ("A Sentimental Novel", 2007), based on his own sexual fantasies about barely pubescent females. The book was translated into English by D.E. Brooke and published in 2014 by Dalkey Archive Press<ref>www.dalkeyarchive.com</ref>, being available for purchase online.<ref>See for example, https://www.amazon.com/Sentimental-Novel-French-Literature/dp/1628970065</ref> | The year before his death, Robbe-Grillet published his last novel, ''Un roman sentimental'' ("A Sentimental Novel", 2007), based on his own sexual fantasies about barely pubescent females. The book was translated into English by D.E. Brooke and published in 2014 by Dalkey Archive Press<ref>www.dalkeyarchive.com</ref>, being available for purchase online.<ref>See for example, https://www.amazon.com/Sentimental-Novel-French-Literature/dp/1628970065</ref> | ||

Revision as of 20:10, 8 February 2023

Alain Robbe-Grillet (born Aug. 18, 1922, Brest, France — died Feb. 18, 2008, Caen, France), was a representative writer and leading theoretician of the nouveau roman ("new novel")[1], French "anti-novel" that emerged in the 1950s, as well as a screenwriter and film director. He is best known in the anglosphere for his screenplay to Last Year at Marienbad (1961)[2], which was nominated for the 1963 Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay[3] and won the Golden Lion award, the highest prize of the Venice Film Festival[4], when it came out in 1961. He also won the prestigious Louis Delluc Prize of 1962[5] for his 1962 film L'Immortelle ("The Immortal One").

The year before his death, Robbe-Grillet published his last novel, Un roman sentimental ("A Sentimental Novel", 2007), based on his own sexual fantasies about barely pubescent females. The book was translated into English by D.E. Brooke and published in 2014 by Dalkey Archive Press[6], being available for purchase online.[7]

The translator's preface makes clear that the book contains detailed fictions of progressive sadism and torture, a growing harem of young females, and a pedagogical master/slave intergenerational relationship between the main 14-year-old female character Gigi, and her father. The translator also points out that the project of translating the original French novel was rejected by numerous American publishers “due to its subject matter, which was considered beyond the pale.” “This pious exhibition of moral opprobrium,” he wrote of American publishers, “can be classified as wrongheaded, springing from a comfort zone of profound and habitual moral hypocrisy.” He maintains that,

“In case the reader might imagine that the book is a one note tale of grim horror, it is important to mention that, odd though it may appear, lighter touches do abound. There is tenderness between the girls, as well as in the development of the father-daughter relationship, even as Gigi submits to, or with her father's collusion delivers, gruesome punishments.”

The English text has been thoughtfully reviewed multiple times.[8] One reviewer explains and quotes from the novel[9]:

"Consisting of 239 numbered paragraphs, “the novel purports to transform into a work of literary fiction,” as the translator states in his thoughtfully argued introduction, “the author’s own avowed catalog of perverse fantasies, which he claimed had remained unchanged since the age of twelve, and that he had been making notes of over the years" [...] "The sadism slowly but surely begins on page four. As Gigi reads aloud, her “master” father is “as attentive to the prosody as he is to posture, [appraising] his lovely schoolgirl without the slightest indulgence, prepared to punish with a single, dry snap of his baton the smallest mistake in reading, rhythm, or even diction.”

"Several other girls become involved in the tale, which is of the story-within-a-story-within-a-story genre. They will be enslaved and tortured each in turn. No details are spared, even in this relatively moderate passage:

Domenica, Domi for short, then drags her prisoner along on a leash, forcing her to advance on her knees, which she is not allowed to bring any closer to one another. If she fails to move quickly enough, or looks like she might be bringing her thighs any closer together, one of the little girls assisting with punishments (young than their leader, even) jabs her bottom with a porker’s needle, ever delighted to add to the sufferings of a disgraced rival being led to her death."

The novel is often compared to the French Marquis de Sade’s famous sexual sadism novel 120 Days of Sodom, with one commentator writing: "the dispassionate way it's told is neither shocking nor horrible. Yet, again, the actions are perfectly monstrous. If you are a fan of Sade, or serious erotic writing that conveys more than sex, this book may be of interest to you."[10] One reviewer compares the novel to Georges Battaille's Story of the Eye (1926),[11] while another interprets the text as an unremarkable commentary on the normalization of violence upon females, historical patriarchy, and how females now learn to participate willingly in violence through the normalization of contemporary BDSM culture.[12]

In interviews, Robbe-Grillet stated that he “loved little girls” but had never acted on his fantasies (Shatz, 2014):

"Yes, he had ‘loved little girls’ since he was 12, but he had never acted on his fantasies. In fact he had ‘mastered’ them. And he continued in this half-facetious, half-moralising vein: ‘someone who writes about his perversion is someone who has control over it.’ […]

The virile looks, however, were deceptive, as his wife Catherine discovered. She was the daughter of Armenians from Iran; they met in 1951 in the Gare de Lyon, as they were both boarding a train to Istanbul. He was instantly taken by her. Barely out of her teens, not quite five feet tall and only forty kilos, Catherine Rstakian ‘looked so young then that everyone thought she was still a child’. She inspired in him (as he later wrote) ‘desperate feelings of paternal love – incestuous, needless to say’. […] ‘His fantasies turned obsessively around sadistic domination of (very) young women, by default little girls,’ she wrote in her memoir of their life together, Alain. He gave her ‘drawings of little girls, bloodied’. (‘Reassure yourself, he never transgressed the limits of the law,’ she adds.) […]

From then on, she says, he ‘isolated himself in an ivory tower populated with prepubescent fantasies, in the pursuit, in his “retirement”, of the waking dreams in his Roman sentimental – reveries of a solitary sadist.’ […]

In Les Derniers jours de Corinthe, the second of these romanesques, he wrote that while working in Martinique he had become infatuated with a ‘pink and blonde’ girl who had ‘the air of a bonbon’; Marianne, the 12-year-old daughter of a local magistrate, would sit on his knee, ‘conscious without doubt’ of the effect these ‘lascivious demonstrations’ had on him."[13]

His crime/detecive novel "The Voyeur", first published in French in 1955 and translated into English in 1958, was awarded the Prix des Critiques. According to wikipedia:

"The Voyeur relates the story of Mathias, a traveling watch salesman who returns to the island of his youth with a desperate objective. As with many of his novels, The Voyeur revolves around an apparent murder: throughout the novel, Mathias unfolds a newspaper clipping about the details of a young girl's murder and the discovery of her body among the seaside rocks. Mathias' relationship with a dead girl, possibly that hinted at in the story, is obliquely revealed in the course of the novel so that we are never actually sure if Mathias is a killer or simply a person who fantasizes about killing. Importantly, the "actual murder," if such a thing exists, is absent from the text. The narration contains little dialogue, and an ambiguous timeline of events."[14]

Robbe-Grillet recieved many prestigious appointments and awards during his working life. In addition to the awards he won, he led the Centre for the Sociology of Literature (Centre de sociologie de la littérature) at the Belgian Université Libre de Bruxelles[15] from 1980 to 1988, and from 1971 to 1995, he was a professor at New York University where he lectured on his own novels. Robbe-Grillet was elected to the Académie française (the French Academy)[16] in 2004.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_Roman

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_Year_at_Marienbad

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_Award_for_Writing_Original_Screenplay

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Lion

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Delluc_Prize

- ↑ www.dalkeyarchive.com

- ↑ See for example, https://www.amazon.com/Sentimental-Novel-French-Literature/dp/1628970065

- ↑ Archive of reviews from completereviews website; see also Zach Maher, Review of A Sentimental Novel (published online April 29, 2014); Elisabeth Zerofsky, Translating a Novel of Sadism, the New Yorker (September 16, 2014). On goodreads, "PaperBird" (March 15, 2015) wrote: "The writing is impeccable, as expected. It's the dynamics between the characters where I feel he fails. Most good porn the heroine undergoes a transformation / degradation / awakening (and sometimes empowerment) of pussy-consciousness, the more 180 from start to finish the better. In this story the heroine at the start is already mostly on board with the father / daughter incest / BDSM program. Her lack of resistance, her eagerness to please, makes me feel like we're missing a couple of juicy "fight" chapters. This leads the role of resistance to a cast of secondary characters we don't really care about, they're so disposable, it just becomes a slaughterfest and you're left feeling as if you were just tested on how much you can stomach. I did however enjoy the conceit of girls found guilty and subjected to arrest and rape by the police, then sexual servitude / torture / death, because of the "crime" of being too beautiful." [...] "By setting all this down, he probably didn't realize how big an arena he was entering and how he could do battle with the inherent enemies of morality and social mores in an interesting way, and so became immediately "dated" as someone two or three steps behind and falling back farther the less prudish / more jaded the world gets. (His solution is to throw spears at everyone, which speaks to how threatened he probably felt, as this was his way of balancing or getting some power back. I could be wrong about this.) At the very least this could be regarded as an artifact for case study of a brilliant 20th century novelist. The richness of detail makes me wonder if there was a dearth of pornographic materials when the author was a kid. Conversely, does anyone nowadays have sexual fantasies this ornate, or even at all, when any variety of porn is just taps away?"

- ↑ John Taylor, Book Review: Grim Light Reading — Alain Robbe-Grillet’s “A Sentimental Novel” (published online June 9, 2014)

- ↑ See "Tosh" on goodreads. Another commentator wrote: "the structure and subject matter is the same as 120 days of Sodom, although not nearly as grim. It’s not a nod, it’s identical." See web comment by "Kevin" dated Oct 4th, 2022, published on John Taylor's website referenced above.

- ↑ On goodreads and amazon, Roger Brunyate wrote: "The French have long had a fascination with literary sadism, especially among intellectual authors. For example, take the very similar Story of the Eye, the 1928 novella by no less than Georges Battaille, the Surrealist and major philosopher. For a long time, "Pauline Réage," the pseudonymous author of Story of O, was suspected of being a member of the Académie Française, perhaps Henri de Montherlant or André Malraux. Robbe-Grillet's book, like de Sade's own and most of their successors, is characterized by a cool refinement at odds with its subject-matter. These horrors do not take place in suburban basements, but in country mansions, private libraries, chateaux whose torture chambers have historical precedents and Latin names. They presuppose an international trade among connoisseurs for condemned criminals (young and female, naturally), vagrant girls, and even unwanted daughters. Everything is described in much the way you would discuss the exotic foods at an ultra-exclusive restaurant."

- ↑ "[P]" wrote (February 25, 2017) on goodreads: I do not believe that the exploring of forbidden, if common, fantasies, nor the sexual gratification of his readers, was Robbe-Grillet’s aim. In fact, far from being a dirty and immoral book, I would argue that one of its principle themes is indoctrination and the harmful effects of what people are exposed to, including pornography. The young girl – who, as noted, has several names, but is mostly called Gigi – is groomed to be her father’s sex slave, is made a willing participant, by virtue of a systematic normalising of the behaviour and acts that please him. She lives, for example, in a house that is essentially a brothel, one that is equipped with torture chambers. She knows no other world. There are, moreover, pictures on the walls showing young girls being tortured; and, as previously noted, she is made to read from texts featuring abuse and torture, and listen to her father’s own anecdotes on the subject. She is even given alcohol and drugs in order to make her pliable. As a consequence of her training, Gigi is the only character in the book who goes on a kind of journey [...] I am most interested in is Gigi’s transformation from slave to master by way of her education. The most persuasive evidence of this is that upon discovery of the pictures of her mother being tortured, Gigi fantasises about Odile being strung up in the same way. She is not pretending out of fear, she has come to find sexual enjoyment in the pain and suffering of others through relentless exposure to it. There are, of course, those who claim that we do not learn in this way, that, to use an analogy, violent computer games cannot create violent people, but I disagree. I do not believe that exposure to unpleasant things has the same effect upon everyone, but I do think that human beings are incredibly suggestible, and our preferences, especially our sexual preferences, are fluid and malleable and are often directly related to our experiences, especially those early in life. It is significant that there is not a single act of aggression or abuse perpetrated against a male in the novel, significant because this too is, for me, one of Robbe-Grillet’s principle preoccupations. Throughout, he repeatedly highlights the cultural and historical persecution and torture of women. He references the martyrdom of Sankt Giesela, the ‘sacrifices listed in the works of Apuleius, Tertullian, and Juvenal’, the rape and murder of women in religious paintings, the burning and disfigurement of concubines who displeased the emperor of the Tang dynasty with their ‘nocturnal activities’, etc. He also notes that girls from the Middle East and Eastern Europe, amongst other places, who have escaped ill-treatment in their home countries, often find themselves sold into sex slavery. Indeed, Robbe-Grillet himself points out that sinners made to perish in front of witnesses are very seldom men, and are most often girls, not mature women. This he puts down to being a consequence of the power being held by men, of, therefore, patriarchy. None of that is particularly profound, or insightful, but it is certainly at odds with the common perception of A Sentimental Novel as the outpourings of a dirty old modernist. As with Octave Mirbeau’s The Torture Garden, Robbe-Grillet appears to be making a comment about humanity-at-large, and our well-documented, natural but lamentable, sadistic and masochistic impulses, impulses that, at least in the case of sadism, we go to great lengths these days to hide."

- ↑ Shatz A. (2014). “At the Crime Scene,” London Review of Books, 36 (15): 21-26.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alain_Robbe-Grillet#Novels

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universit%C3%A9_Libre_de_Bruxelles

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acad%C3%A9mie_fran%C3%A7aise