One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

Research: The effects of pornography

| ||||||||||||

| Part of NewgonWiki's research project | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Template: Research - This template |

The harm thought to be caused to minors by pornography and other "inappropriate content" is not supported by any properly controlled outcome studies or other scientific evidence. Morality and socialization of youth are instead the rationales given for policing this content. Throughout much of the professional literature, preventing minors from accessing this material is still assumed, a-priori, to be a rightful and realistic goal. Many of the reports commissioned by governments and NGOs use correlational studies, which do not establish cause and effect, and are plagued with negative value judgments concerning "high risk behaviors" and "permissive attitudes". This lack of evidence casts doubt upon the use of imprecise and expensive internet filters by central governments, and the insistence of some governments upon self-regulatory ISP models.

- Researchers, Educators and Therapists in Support of Appellee in United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group (published March, 2003). Brief Amici Curiae of Sexuality Scholars. No. 98-1682 (Oct. Term 1998), p. 8.

- "Most scholars in the field of sexuality agree that there is no basis to believe sexually explicit words or images … in and of themselves cause psychological harm to the great majority of young people."

- UNICEF (2021). Digital Age Assurance Tools and Children’s Rights Online across the Globe. A Discussion Paper.

- "There are several different kinds of risks and harms that have been linked to children’s exposure to pornography, but there is no consensus on the degree to which pornography is harmful to children. [...] As discussed above, the evidence is inconsistent, and there is currently no universal agreement on the nature and extent of the harm caused to children by viewing content classified as pornography. However, policymakers in several countries have deemed that children should not be able to access commercial pornography websites designed for users aged over 18."

- Becker, J., & Stein, R. M. (1991). Is sexual erotica associated with sexual deviance in adolescent males? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 14(1-2), 85–95.

- "This study did not demonstrate a relationship between sexually explicit material and number of victims. Furthermore, the majority of youngsters surveyed did not feel that using sexually explicit material played a part in the commission of a sexual offense."

- NCAC (March, 2001). "White Paper Submitted to the Committee on Tools and Strategies for Protecting Kids From Pornography and Their Applicability to Other Inappropriate Internet Content.

- "In 1986, the Surgeon General's Workshop on Pornography and Public Health concluded that there is no scientific basis to believe that minors are adversely affected by pornography. Indeed, it noted that many psychologists believe young children are unaffected by pornography because they lack "the cognitive or emotional capacities needed to comprehend it." In the end, these experts said, "it is really rather difficult to say much definitive about the possible effects of exposure to pornography on children." The more widely publicized majority report that same year of the Attorney General's Commission on Pornography (the Meese Commission) did not disagree. The Meese Commission acknowledged that its concerns about minors' access to pornography were based on morality, not science. In the Playboy Entertainment case, expert witnesses for both the government and Playboy testified at trial that there is no empirical body of evidence of harm to minors from exposure to pornography. [...] Dr. Richard Green, founding president of the International Academy of Sex Research and author of Sexual Science and the Law, testified that none of the available literature—including comparisons of the amount of erotica available in different countries, studies of sex offenders, laboratory experiments on pornography and violence, clinical experience worldwide, and research on people who as children had witnessed the "primal scene" of sexual intercourse—supports the notion that exposure to sexual explicitness is psychologically harmful to youth. In 25 years of clinical practice, Dr. Green had not encountered psychological problems stemming from pornography. The government in Playboy Entertainment initially attempted to establish harm to minors by offering testimony from Dr. Diana Elliott, who operated a clinic for abused children in California. The three-judge trial court rejected Dr. Elliott's testimony as weak, anecdotal, and "possibly misleading."8 Later, the government presented a new expert witness, Dr. Elissa Benedek, who opined that sexually explicit television might produce an assortment of harmful effects but acknowledged that she knew of no scientific literature or clinical studies supporting her belief, and that in her 30 years of psychiatric practice, nobody had come to her with a complaint about sexual images. The judges were unimpressed with Benedek's testimony. "We are troubled," they wrote, "by the absence of harm presented both before Congress and before us that the viewing of signal bleed of sexually explicit programming causes harm to children.""

- Diamond, M., & Uchiyama, A. (1999). Pornography, Rape, and Sex Crimes in Japan. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–22.

- "Most frequently, as it was found in the 1960s before the influx of sexually explicit materials into the United States, those who committed sex crimes typically had less exposure to SEM in their background than others and the offenders generally were individuals deeply religious and socially and politically conservative (Gebhard, Gagnon, Pomeroy, & Christenson, 1965). Since then, most researchers have found similarly. The upbringing of sex offenders was usually sexually repressive, often they had an overtly religious background and held rigid conservative attitudes toward sexuality (Conyers & Harvey, 1996; Dougher, 1988); their upbringing had usually been ritualistically moralistic and conservative rather than permissive. During adolescence and adulthood, sex offenders were generally found not to have used erotic or pornographic materials any more than any other groups of individuals or even less so (Goldstein & Kant, 1973, Propper, 1972). Walker (1970) reported that sex criminals were several years older than non-criminals before they first saw pictures of intercourse

- [...]

- "However, there are no specific child pornography laws in Japan and SEM depicting minors are readily available and widely consumed. [...] The most dramatic decrease in sex crimes was seen when attention was focused on the number and age of rapists and victims among younger groups (Table 2). We hypothesized that the increase in pornography [in general], without age restriction and in comics, if it had any detrimental effect, would most negatively influence younger individuals. Just the opposite occurred. The number of juvenile offenders dramatically dropped every period reviewed from 1,803 perpetrators in 1972 to a low of 264 in 1995; a drop of some 85% (Table 1). The number of victims also decreased particularly among the females younger than 13 (Table 2). In 1972, 8.3% of the victims were younger than 13. In 1995 the percentage of victims younger than 13 years of age dropped to 4.0%."

Cause or Confound?

The relationship between pornography viewing and "subsequent" behavior is a classic chicken and egg situation, in that causative direction can never be established when observing events in an uncontrolled, real-life scenario. This is already widely known in relation to television viewing. For example, a 1991 study found that of 391 junior high school students, those who watched sexual TV shows were more likely to have become sexually active in the preceding year. The researchers were "unable to determine which came first—sexual intercourse or a proclivity for viewing sexual activity on television."[1] Regarding pornography, it is even more likely that behaviors are correlated with viewing habits as a result of pre-existing character traits and ongoing socialization. This may be for a number of reasons:

- Exposure to pornography is typically a self-directed act that takes place in private. A young person's socialization consists of numerous experiences, of which pornography consumption is but one tiny part.

- In the modern world, free pornography is a highly categorized and subdivided medium, which can be immediately filtered by genre, fetish or other special interest. This, again, means that pornography exposure can be highly self-directed, and is likely to correlate with pre-existing interests and values, rather than influencing them.

Jeffrey Arnett, documenting a similar correlation between adolescents' reckless behavior and preference for violent music, identified "sensation seeking" as the confound that explained both the preference and the behavior. Arnett added that "adolescents who like heavy metal music listen to it especially when they are angry and that the music has the effect of calming them down and dissipating their anger."[2]

At the social scale, there is correlational evidence linking wider availability of pornography with reductions in sexual offending, for example in Denmark, as documented in our Youth Erotica article, and Japan.[3] This linkage between porn, sexual "responsibility" and celibacy is also supported by evidence following the advent of the internet.[4]

Subjective reactions

Studies into subjective reactions of children to sexual content are few and far between, and likely biased by bad questionnaire design, unwarranted focus on first exposure, and the childrens' own fear of censure, and giving the "wrong" answer. The results are still surprisingly diverse in their nature, with most minors recalling a positive or neutral reaction to such material.

- Smahel, D., H. Machackova, G. Mascheroni, L., Dedkova, E., Staksrud, K., Ólafsson, S. Livingstone and U. Hasebrink (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries, EU Kids Online, London School of Economics, London.

- "being exposed to sexual images can be perceived both as a positive and a negative experience, depending on the context and the individual child. How sexual images are perceived can also be influenced by intentionality – the response to exposure due to seeking out sexual images could differ from unexpected exposure [...] in most of the countries, most of the children who saw some sexual image were neither upset nor happy (Ave = 44%), ranging between 27% (Switzerland) and 72% (Lithuania). In contrast, between 10% (Lithuania) and 40% (Switzerland) of the children were fairly or very upset (Ave = 22%), while feeling happy after seeing sexual images was reported by a similar number of children across the countries, ranging between 3% in Estonia and 39% in Spain."

Excerpt Graphic Library

The Excerpt Graphic Library on Youth Sexuality has some useful information related to this topic. These can be accessed, saved and uploaded into shortform social media debates where character limits are in force.

-

Declining rates of sexual activity among youth (YRBS)

-

Various research on Teen Pregnancy correlational nonsense

-

Sexual Repression - effects on the young

-

Sexual Behavior in youth and its effects

-

Reading on child sexuality

-

Some reading on the effects of intimacy

-

Jane Rule on treatment of youth

-

NCAC: Justification for protecting children from porn has always been moral

-

Lancet Global Health: Maternal mortality by region, and across 144 countries

-

Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the USA from 1998 to 2005

Competences are also somewhat related:

-

Basic brain aging primer

-

Teen Brain research summary

-

Age chauvinism

-

BJ Casey

-

Joseph Bronski

-

Full Brain Size and adult-like competences in early childhood

-

Development of reasoning ability in early childhood (Moshman, 2005)

-

Early development of brain - Del Giudice

-

White and Gray Matter levels - Del Giudice (2017)

-

Bethlehem et al, 2022, brain volumes and matter levels by age

-

Giedd 1999 brain matter curves by age

-

Mills et al: Adolescent brains indistinguishable from adult. Variance in gray matter between individuals is far greater than any changes over time.

-

John Raven - Intelligence hits a peak in the mid teens, then plateaus and declines (the decline may have been at least in part due to poorer education in the interwar period).

-

John Raven - Intelligence hits a peak in the mid teens, then plateaus (note improvement in scores obtained in the 1970s)

-

Moshman on common fallacies of teen brain development

-

Moshman continued

-

Moshman continued

-

Laurence Steinberg (2008)

-

Epstein reviewed, plus other references - raw intelligence peak 13-15 y/o

-

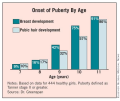

2020 meta-analysis on the age of Thelarche (breast budding in girls - start of puberty). Similar for first period.

-

Conclusions of the aforementioned 2020 meta-analysis

-

Physical development - Tanner stages reached considerably earlier than commonly supposed

-

Physical development - Ages of pubertal development lower than commonly stated

-

Girls developing sexual features almost completely by 11

References

- ↑ Jane Brown & Susan Newcomer, "Television Viewing and Adolescents' Sexual Behavior," J. of Homosexuality 77, 84, 88 (1991)

- ↑ Jeffrey Arnett, "The Soundtrack of Restlessness—Musical Preferences and Reckless Behavior Among Adolescents," 7 J. Adol. Rsrch 313, 328 (1992)

- ↑ Diamond, M., & Uchiyama, A. (1999). Pornography, Rape, and Sex Crimes in Japan. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–22.

- ↑ Psychology Today: Does Pornography cause social harm?