One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

Gabrielle Russier: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

The Admins (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

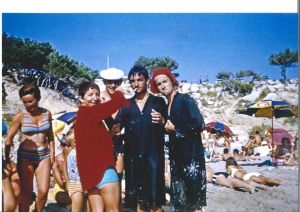

'''Gabrielle Russier''', (Born April 29, 1937, in Paris - Died September 1, 1969, in Marseille), was an associate professor of literature. At 31-years-old with two children, following the stigmatization of a [[Consent|consensual]] romantic / sexual relationship with '''Christian Rossi''' - one of her sixteen-year-old students - Gabrielle and her romantic life became the subject of nationwide controversy and debate. Their case is a historical [[Accounts_and_Testimonies|positive experience]] between a teacher and student who were legally adult and minor ([[AAM]]), in which the couple were subjected to [[Research:_Secondary_Harm|secondary / iatrogenic harm]], leading to psychological distress and death. | __NOTOC__[[File:Gabrielle-lighting-Christian-Rossis-cigarette-on-Sainte-Croix-beach-in-Martigues-July-1968.jpg|thumb|Gabrielle Russier, pictured lighting Christian Rossi's cigarette on Sainte-Croix beach in Martigues, in July 1968 (See Gallery below for more)]]'''Gabrielle Russier''', (Born April 29, 1937, in Paris - Died September 1, 1969, in Marseille), was an associate professor of literature. At 31-years-old with two children, following the stigmatization of a [[Consent|consensual]] romantic / sexual relationship with '''Christian Rossi''' - one of her sixteen-year-old students - Gabrielle and her romantic life became the subject of nationwide controversy and debate. Their case is a historical [[Accounts_and_Testimonies|positive experience]] between a teacher and student who were legally adult and minor ([[AAM]]), in which the couple were subjected to [[Research:_Secondary_Harm|secondary / iatrogenic harm]], leading to psychological distress and death. | ||

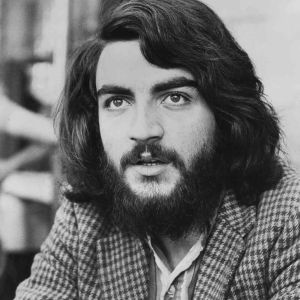

A ''New York Times'' article describes Christian as "a big, bearded, militant Maoist who looked at least 25", whereas "Mrs. Russier was tiny and frail, like a child with an unusually grave face."<ref>Anatole Broyard, [https://www.nytimes.com/1971/12/01/archives/a-truly-french-tragicomedy.html A Truly French Tragicomedy] (''The New York Times'', Dec. 1, 1971).</ref> Christian's parents were professors and friends with Gabrielle | A ''New York Times'' article describes Christian as "a big, bearded, militant Maoist who looked at least 25", whereas "Mrs. Russier was tiny and frail, like a child with an unusually grave face."<ref name="Broyard">Anatole Broyard, [https://www.nytimes.com/1971/12/01/archives/a-truly-french-tragicomedy.html A Truly French Tragicomedy] (''The New York Times'', Dec. 1, 1971).</ref> Christian's parents were professors and friends with Gabrielle, but objected to and criminalized their relationship after Gabrielle formally requested their permission to live together. After sending Christian away to a boarding school which failed to keep the couple apart, the parents "went to court because they were afraid that Mrs. Russier would take Christian away from them."<ref name="Broyard" /> The massive publicity following her arrest, likened to the [[wikipedia:Dreyfus_affair|Dreyfus affair]],<ref name="Broyard" /> led to her prison letters being read and performed on the radio, the creation of sympathetic songs, numerous books, and multiple films under the name ''Mourir d'aimer'' (Dying to Love), including a popular film by André Cayatte which saw 5.9 million admissions in theaters. Later in 2009, a television film by Josée Dayan was strongly criticized by former pastor Michel Viot, who had presided over Gabrielle's funeral and knew Christian personally. He considered the film's message to have distorted the love story between a teacher and her student.<ref>[https://fr-m-wikipedia-org.translate.goog/wiki/Mourir_d%27aimer_(film,_1971)?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=wapp Dying to Love (1971)] by André Cayatte.</ref><ref>[https://fr-m-wikipedia-org.translate.goog/wiki/Mourir_d%27aimer_(t%C3%A9l%C3%A9film,_2009)?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=wapp Dying to Love (TV movie, 2009)], directed by Josée Dayan.</ref> [[File:Christian-Rossi-18-in-Paris-May-27-1970.jpg|thumb|Christian Rossi pictured at 18 years old in Paris, May 27th 1970.]] After months of controversy and preventive detention, Gabrielle Russier was tried, fined and given a suspended sentence of 12 months. However, within 30 minutes of the verdict, the public prosecutor moved for a retrial and stiffer sentence. Before the retrial could take place, Gabrielle committed suicide by filling her apartment with gas. | ||

These events were of such national importance that the newly-elected president [ | These events were of such national importance that the newly-elected president [[Wikipedia:Georges_Pompidou|Georges Pompidou]], when asked about the affair on a televised Presidential press conference, recited a poem by Paul Éluard about a girl martyred by society because she loved the wrong person. Before her death, Gabrielle reportedly wrote to Christian: "''You were the only man I ever knew.''" | ||

Rossi, who had been forced / committed to a psychiatric asylum by his parents, left the asylum and was taken in and hidden by pastor Michel Viot who had conducted Gabrielle's funeral. In February 1970, he provided an update to the press: | |||

<blockquote>''We told a lot of lies around our affair, we wanted to give her ''[Gabrielle]'' the image of a teacher who had bewitched his young student. The reality was very different. There was never the traditional teacher-student relationship between her and me. She came with us skiing. We were dating. This is how we gradually grew closer. But it's not because she was my teacher that we liked each other, we could have met anywhere else.''</blockquote> | |||

On September 1, 1971, he gave an exclusive interview with ''Nouvel Observateur'': | |||

<blockquote>''It wasn’t a passion at all. It was love. Passion is not lucid. Now, it was lucid. ''[...]'' The ''[two years]'' of memories that she left me, she left them to me, I don't have to tell them. I feel them. I experienced them alone. ''[...]'' The rest, people know: it's a woman called Gabrielle Russer. We loved each other, we put her in prison, she killed herself. It's simple.''</blockquote> | |||

The scholarly article "''The Policing of Desire in the Gabrielle Russier Affair''" (2005)<ref>Keith Reader, [https://sci-hub.hkvisa.net/10.1177/0957155805049563 The Policing of Desire in the Gabrielle Russier Affair], ''French Cultural Studies'', 16(1): 005–020.</ref> recounts the event and gives historical perspective on a "now largely forgotten but still important part of the [ | The scholarly article "''The Policing of Desire in the Gabrielle Russier Affair''" (2005)<ref>Keith Reader, [https://sci-hub.hkvisa.net/10.1177/0957155805049563 The Policing of Desire in the Gabrielle Russier Affair], ''French Cultural Studies'', 16(1): 005–020.</ref> recounts the event and gives historical perspective on a "now largely forgotten but still important part of the [[wikipedia:May_68|history of 1968]] and its aftermath". The 1971 book "''The Affair of Gabrielle Russier''" provides important historical context.<ref>''The Affair of Gabrielle Russier'' (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1971). Preface by Raymond Jean; Introduction by Mavis Gallant. Letters and Preface translated from the French by Chislaine Boulanger.</ref> The book contains English-translated letters from Gabrielle to Christian, a preface by a professor who knew Gabrielle (Raymond Jean), and an introduction which reproduces an article from ''The New Yorker'' by popular author Mavis Gallant.<ref>[https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1971/06/26/immortal-gatito The Case of Gabrielle Russier], ''The New Yorker'' (1971).</ref> Available online, Gallant explains: | ||

<blockquote>''She was not at all like other teachers. When she walked into the Lycée Saint-Exupéry in Marseille in October, 1967, to take over three classes in French literature, the students thought she was a new girl. She was thirty, but looked eighteen. She was tiny, just over five feet tall, and weighed about a hundred pounds. Her hair was cropped short, as boys’ hair used to be. ''[...]'' Her students worshipped her. They called her Gatito, which is Spanish for “little cat,” and they used the familiar “tu” in addressing her.'' | |||

''This is so unusual from pupil to teacher in France that it just touches the implausible. Relations are formal in a lycée. ''[...]'' One of the complaints students have is that their teachers are remote as planets and that they can never discuss anything with them, not even their work. Gabrielle, on the contrary, wanted to be one of them. She based much of her social life on their movies, their outings, their songs. She invited them to her apartment to talk and listen to records. The students loved this''.</blockquote> | |||

==Details from Wikipedia== | |||

We freely adapt from Wikipedia the following information: | |||

'''Meeting and rapprochement, 1968''' | |||

Gabrielle met Christian, born in January 1952, when he was fifteen years old. They join the demonstrations together at the end of May 68. The pair began an affair when he is at the end of second grade. During the summer holidays, Christian tells them that he is hitchhiking with a high school friend to Italy and Germany. Gabrielle traveled with Christian, aged 16 and a half, to these two countries. | |||

'''Referral to the judge, October 1968''' | |||

At the start of the school year, Christian's parents ask him to break up, but he refuses and moves in with Gabrielle. On October 15, 1968, the parents go to the children's judge. The latter finds a compromise: send the young man to Argelès high school, as a boarding student, while letting Gabrielle write to him and see him on All Saints' Day. However, Gabrielle's letters were intercepted, so much so that Christian threatens to commit suicide. As she comes to pick him up, the police arrest Gabrielle. On November 16, Christian ran away and is hosted by a high school friend. Gabrielle joins him. Fifteen days later, Christian's father filed a complaint for kidnapping and embezzlement of a minor. | |||

'''Incarcerations: December 1968 and April 1969''' | |||

The investigating judge Bernard Palanque, called while he was not on duty because the case was considered “delicate”, indicted Gabrielle for embezzlement of a minor and ordered her incarceration at Baumettes prison for the first time. | |||

Christian Rossi's parents decide to place him in different institutes, then have him interned in the ''L'Émeraude'' psychiatric clinic, where he undergoes a sleep treatment for three weeks. Despite these events, Gabrielle and Christian meet again and Christian ends up running away. On April 14 , 1969, Gabrielle was imprisoned again, first for a few days, then for five weeks from April 25 to June 13, 1969 for refusing to reveal where Christian was hiding. She ultimately remained in detention for fifty days. | |||

On June 23, the University of Aix-en-Provence rejected Gabrielle's application for a position as a linguistics assistant. | |||

'''Reaction of Georges Pompidou''' | |||

On September 22, 1969, at the end of his press conference, the President of the Republic Georges Pompidou who, during the electoral campaign, promised the French "a new society", questioned on the affair by Jean-Michel Royer, journalist at RMC, responds : “I won't tell you everything I thought about this matter. Or even what I did. As for what I felt, like many, eh! understand well ''whoever wants, Me, my remorse, it was the reasonable victim in the eyes of a lost child, the one who resembles the dead who died to be loved''", thus quoting Paul Éluard and his verses dedicated to shorn women at the Liberation. He then leaves the room. | |||

On November 25, 1969, a petition was submitted to the Minister of Justice, René Pléven denouncing what they see as an "Inquisition" in the Russier affair. It is signed by personalities from all walks of life, including Nobel Prize winners Jacques Monod, François Jacob, Alfred Kastler, and the journalist André Frossard. | |||

'''Influence on society''' | |||

Five days after her death, filmmaker Jacques Deray announced his intention to make a film telling the story of Gabrielle Russer. Following the preventive detentions of Gabrielle which many deemed abusive, the Minister of Justice René Pleven announced in October 1969 a reform of preventive detention. | |||

In 2017, ''Libération'' published a column by the editor Jean-Marc Savoye titled "La Revanche de Gabrielle", pointing out a similarity in the story of Gabrielle Russier with that of the new President Emmanuel Macron who, as a fifteen-year-old high school student, is living a story of love with his teacher Brigitte Trogneux. | |||

==Gallery== | |||

<gallery> | |||

File:Russier-and-Rossi-film.jpg|Russier and Rossi depicted in film. | |||

File:Who-kills-or-the-Gabrielle-Russer-affair-April-1970-Exhibition-Paris-Museum-of-Modern-Art-By-Malassis-cooperative.jpg|Exhibition in April 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art in the city of Paris “Who kills? or the Gabrielle Russer affair. Malassis cooperative. | |||

File:September-1967-Christian-Rossi-is-in-the-back-row-second-from-the-right.jpg|The second C class at the start of the school year in September 1967. Christian Rossi is in the back row, second from the right. | |||

</gallery> | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Latest revision as of 14:13, 2 December 2023

Gabrielle Russier, (Born April 29, 1937, in Paris - Died September 1, 1969, in Marseille), was an associate professor of literature. At 31-years-old with two children, following the stigmatization of a consensual romantic / sexual relationship with Christian Rossi - one of her sixteen-year-old students - Gabrielle and her romantic life became the subject of nationwide controversy and debate. Their case is a historical positive experience between a teacher and student who were legally adult and minor (AAM), in which the couple were subjected to secondary / iatrogenic harm, leading to psychological distress and death. A New York Times article describes Christian as "a big, bearded, militant Maoist who looked at least 25", whereas "Mrs. Russier was tiny and frail, like a child with an unusually grave face."[1] Christian's parents were professors and friends with Gabrielle, but objected to and criminalized their relationship after Gabrielle formally requested their permission to live together. After sending Christian away to a boarding school which failed to keep the couple apart, the parents "went to court because they were afraid that Mrs. Russier would take Christian away from them."[1] The massive publicity following her arrest, likened to the Dreyfus affair,[1] led to her prison letters being read and performed on the radio, the creation of sympathetic songs, numerous books, and multiple films under the name Mourir d'aimer (Dying to Love), including a popular film by André Cayatte which saw 5.9 million admissions in theaters. Later in 2009, a television film by Josée Dayan was strongly criticized by former pastor Michel Viot, who had presided over Gabrielle's funeral and knew Christian personally. He considered the film's message to have distorted the love story between a teacher and her student.[2][3]

After months of controversy and preventive detention, Gabrielle Russier was tried, fined and given a suspended sentence of 12 months. However, within 30 minutes of the verdict, the public prosecutor moved for a retrial and stiffer sentence. Before the retrial could take place, Gabrielle committed suicide by filling her apartment with gas.

These events were of such national importance that the newly-elected president Georges Pompidou, when asked about the affair on a televised Presidential press conference, recited a poem by Paul Éluard about a girl martyred by society because she loved the wrong person. Before her death, Gabrielle reportedly wrote to Christian: "You were the only man I ever knew."

Rossi, who had been forced / committed to a psychiatric asylum by his parents, left the asylum and was taken in and hidden by pastor Michel Viot who had conducted Gabrielle's funeral. In February 1970, he provided an update to the press:

We told a lot of lies around our affair, we wanted to give her [Gabrielle] the image of a teacher who had bewitched his young student. The reality was very different. There was never the traditional teacher-student relationship between her and me. She came with us skiing. We were dating. This is how we gradually grew closer. But it's not because she was my teacher that we liked each other, we could have met anywhere else.

On September 1, 1971, he gave an exclusive interview with Nouvel Observateur:

It wasn’t a passion at all. It was love. Passion is not lucid. Now, it was lucid. [...] The [two years] of memories that she left me, she left them to me, I don't have to tell them. I feel them. I experienced them alone. [...] The rest, people know: it's a woman called Gabrielle Russer. We loved each other, we put her in prison, she killed herself. It's simple.

The scholarly article "The Policing of Desire in the Gabrielle Russier Affair" (2005)[4] recounts the event and gives historical perspective on a "now largely forgotten but still important part of the history of 1968 and its aftermath". The 1971 book "The Affair of Gabrielle Russier" provides important historical context.[5] The book contains English-translated letters from Gabrielle to Christian, a preface by a professor who knew Gabrielle (Raymond Jean), and an introduction which reproduces an article from The New Yorker by popular author Mavis Gallant.[6] Available online, Gallant explains:

She was not at all like other teachers. When she walked into the Lycée Saint-Exupéry in Marseille in October, 1967, to take over three classes in French literature, the students thought she was a new girl. She was thirty, but looked eighteen. She was tiny, just over five feet tall, and weighed about a hundred pounds. Her hair was cropped short, as boys’ hair used to be. [...] Her students worshipped her. They called her Gatito, which is Spanish for “little cat,” and they used the familiar “tu” in addressing her. This is so unusual from pupil to teacher in France that it just touches the implausible. Relations are formal in a lycée. [...] One of the complaints students have is that their teachers are remote as planets and that they can never discuss anything with them, not even their work. Gabrielle, on the contrary, wanted to be one of them. She based much of her social life on their movies, their outings, their songs. She invited them to her apartment to talk and listen to records. The students loved this.

Details from Wikipedia

We freely adapt from Wikipedia the following information:

Meeting and rapprochement, 1968

Gabrielle met Christian, born in January 1952, when he was fifteen years old. They join the demonstrations together at the end of May 68. The pair began an affair when he is at the end of second grade. During the summer holidays, Christian tells them that he is hitchhiking with a high school friend to Italy and Germany. Gabrielle traveled with Christian, aged 16 and a half, to these two countries.

Referral to the judge, October 1968

At the start of the school year, Christian's parents ask him to break up, but he refuses and moves in with Gabrielle. On October 15, 1968, the parents go to the children's judge. The latter finds a compromise: send the young man to Argelès high school, as a boarding student, while letting Gabrielle write to him and see him on All Saints' Day. However, Gabrielle's letters were intercepted, so much so that Christian threatens to commit suicide. As she comes to pick him up, the police arrest Gabrielle. On November 16, Christian ran away and is hosted by a high school friend. Gabrielle joins him. Fifteen days later, Christian's father filed a complaint for kidnapping and embezzlement of a minor.

Incarcerations: December 1968 and April 1969

The investigating judge Bernard Palanque, called while he was not on duty because the case was considered “delicate”, indicted Gabrielle for embezzlement of a minor and ordered her incarceration at Baumettes prison for the first time.

Christian Rossi's parents decide to place him in different institutes, then have him interned in the L'Émeraude psychiatric clinic, where he undergoes a sleep treatment for three weeks. Despite these events, Gabrielle and Christian meet again and Christian ends up running away. On April 14 , 1969, Gabrielle was imprisoned again, first for a few days, then for five weeks from April 25 to June 13, 1969 for refusing to reveal where Christian was hiding. She ultimately remained in detention for fifty days.

On June 23, the University of Aix-en-Provence rejected Gabrielle's application for a position as a linguistics assistant.

Reaction of Georges Pompidou

On September 22, 1969, at the end of his press conference, the President of the Republic Georges Pompidou who, during the electoral campaign, promised the French "a new society", questioned on the affair by Jean-Michel Royer, journalist at RMC, responds : “I won't tell you everything I thought about this matter. Or even what I did. As for what I felt, like many, eh! understand well whoever wants, Me, my remorse, it was the reasonable victim in the eyes of a lost child, the one who resembles the dead who died to be loved", thus quoting Paul Éluard and his verses dedicated to shorn women at the Liberation. He then leaves the room.

On November 25, 1969, a petition was submitted to the Minister of Justice, René Pléven denouncing what they see as an "Inquisition" in the Russier affair. It is signed by personalities from all walks of life, including Nobel Prize winners Jacques Monod, François Jacob, Alfred Kastler, and the journalist André Frossard.

Influence on society

Five days after her death, filmmaker Jacques Deray announced his intention to make a film telling the story of Gabrielle Russer. Following the preventive detentions of Gabrielle which many deemed abusive, the Minister of Justice René Pleven announced in October 1969 a reform of preventive detention.

In 2017, Libération published a column by the editor Jean-Marc Savoye titled "La Revanche de Gabrielle", pointing out a similarity in the story of Gabrielle Russier with that of the new President Emmanuel Macron who, as a fifteen-year-old high school student, is living a story of love with his teacher Brigitte Trogneux.

Gallery

-

Russier and Rossi depicted in film.

-

Exhibition in April 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art in the city of Paris “Who kills? or the Gabrielle Russer affair. Malassis cooperative.

-

The second C class at the start of the school year in September 1967. Christian Rossi is in the back row, second from the right.

See also

- Alain Robbe-Grillet - One of the authors whose writing Russier had written on as part of her doctoral degree.

- Guy Hocquenghem - French revolutionary Leftist who published sympathetically on pedophilia and intergenerational sexuality.

- Pat Sikes - British professor who has experienced and written on positive teacher-student romantic-sexual relationships.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Anatole Broyard, A Truly French Tragicomedy (The New York Times, Dec. 1, 1971).

- ↑ Dying to Love (1971) by André Cayatte.

- ↑ Dying to Love (TV movie, 2009), directed by Josée Dayan.

- ↑ Keith Reader, The Policing of Desire in the Gabrielle Russier Affair, French Cultural Studies, 16(1): 005–020.

- ↑ The Affair of Gabrielle Russier (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1971). Preface by Raymond Jean; Introduction by Mavis Gallant. Letters and Preface translated from the French by Chislaine Boulanger.

- ↑ The Case of Gabrielle Russier, The New Yorker (1971).