One of our staff members is contributing considerably to a News Archiving service at Mu. Any well educated (Masters, PhD or above) users who wish to make comments on news sites, please contact Jim Burton directly rather than using this list, and we can work on maximising view count.

Research: Prevalence of Harm and Negative Outcomes: Difference between revisions

The Admins (talk | contribs) tor friendly ipt |

No edit summary |

||

| (183 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{research}} | {{research}}__NOTOC__ | ||

:''[https://web.archive.org/web/20211021023155/https://cchain2021.tiiny.site/ Web Archive (within series)]'' | |||

Research (much of it outdated) investigating CSA as a clinical/legal/traumatic phenomenon, using similarly obtained samples is wrongly generalized by practitioners and educators to the entire population. Society is not an enormous clinic, so why should we assume these studies are representative? | |||

This article pools mainly nonclinical, nonlegal and nontraumatic sampled research articles documenting the prevalence of harm. [[Rind et al]] (1998) confirmed that CSA is not a reliable predictor of later maladjustment, when other factors are accounted for. [[Research:_Secondary_Harm#Self-appraisal_of_abuse,_Self-Perception_and_%22Consent%22|Self-perception of (simple) consent]] is also a strong predictor of indifferent or positive outcomes. These results have been re-affirmed as recently as 2021 by Daly. On the other hand, non-consent is even correlated with negative outcomes for adult men victimized by women.<ref>[https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10508-023-02717-0 Madjlessi, J., Loughnan, S. Male Sexual Victimization by Women: Incidence Rates, Mental Health, and Conformity to Gender Norms in a Sample of British Men. Arch Sex Behav (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02717-0]</ref> | |||

As a side note, prevalence of CSA is widely held to be "1 in 10" for the purpose of clarity in victim advocacy, but varies by gender and depending on definition of abuse (peer vs adults only, etc). None of these are settled debates.<ref>[https://www.d2l.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Updated-Prevalence-White-Paper-1-25-2016_2020.pdf Darkness To Light]</ref> | |||

==Outcomes== | ==Outcomes== | ||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]]; Tromovitch, Philip; Bauserman, Robert (1998). "A Meta-Analytic Examination of Assumed Properties of Child Sexual Abuse Using College Samples, | *'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]]; Tromovitch, Philip; Bauserman, Robert (1998). [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.22 "A Meta-Analytic Examination of Assumed Properties of Child Sexual Abuse Using College Samples"], ''Psychological Bulletin'', 124(1), 22-53, doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.22 ''' | ||

*:'''Note:''' Successfully replicated by Ulrich<ref>[https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/wp-content/uploads/A-replication-of-the-meta-analytic-examination-of-child-sexual-abuse-by-Rind-Tromovitch-and-Bauserman.pdf Ulrich - A replication of the meta-analytic examination of child sexual abuse by Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman (1998)]</ref> and Daly below. | |||

*:"Many lay persons and professionals believe that child sexual abuse (CSA) causes intense harm, regardless of gender, pervasively in the general population. The authors examined this belief by reviewing 59 studies based on college samples. Meta-analyses revealed that students with CSA were, on average, slightly less well adjusted than controls. However, this poorer adjustment could not be attributed to CSA because [[Research: Family Environment|family environment]] (FE) was consistently confounded with CSA, FE explained considerably more adjustment variance than CSA, and CSA-adjustment relations generally became nonsignificant when studies controlled for FE. Self-reported reactions to and effects from CSA indicated that negative effects were neither pervasive nor typically intense, and that men reacted much less negatively than women. The college data were completely consistent with data from national samples. [...] | *:"Many lay persons and professionals believe that child sexual abuse (CSA) causes intense harm, regardless of gender, pervasively in the general population. The authors examined this belief by reviewing 59 studies based on college samples. Meta-analyses revealed that students with CSA were, on average, slightly less well adjusted than controls. However, this poorer adjustment could not be attributed to CSA because [[Research: Family Environment|family environment]] (FE) was consistently confounded with CSA, FE explained considerably more adjustment variance than CSA, and CSA-adjustment relations generally became nonsignificant when studies controlled for FE. Self-reported reactions to and effects from CSA indicated that negative effects were neither pervasive nor typically intense, and that men reacted much less negatively than women. The college data were completely consistent with data from national samples. [...] | ||

*:Fifteen studies presented data on participants' retrospectively recalled immediate reactions to their CSA experiences that were classifiable as positive, neutral, or negative. Overall, 72% of female experiences, but only 33% of male experiences, were reported to have been negative at the time. On the other hand, 37% of male experiences, but only 11% of female experiences, were reported as positive. [...] Seven female and three male samples contained reports of positive, neutral, and negative current reflections (i.e., current feelings) about CSA experiences. Results were similar to retrospectively recalled immediate reactions, with 59% of 514 female experiences being reported as negative compared with 26% of 118 male experiences. Conversely, 42% of current reflections of male experiences, but only 16% of female experiences, were reported as positive. [...] The overall picture that emerges from these self-reports is that (a) the vast majority of both men and women reported no negative sexual effects from their CSA experiences; (b) lasting general negative effects were uncommon for men and somewhat more common for women, although still comprising only a minority; and (c) temporary negative effects were more common, reported by a minority of men and a minority to a majority of women." | *:Fifteen studies presented data on participants' retrospectively recalled immediate reactions to their CSA experiences that were classifiable as positive, neutral, or negative. Overall, 72% of female experiences, but only 33% of male experiences, were reported to have been negative at the time. On the other hand, 37% of male experiences, but only 11% of female experiences, were reported as positive. [...] Seven female and three male samples contained reports of positive, neutral, and negative current reflections (i.e., current feelings) about CSA experiences. Results were similar to retrospectively recalled immediate reactions, with 59% of 514 female experiences being reported as negative compared with 26% of 118 male experiences. Conversely, 42% of current reflections of male experiences, but only 16% of female experiences, were reported as positive. [...] The overall picture that emerges from these self-reports is that (a) the vast majority of both men and women reported no negative sexual effects from their CSA experiences; (b) lasting general negative effects were uncommon for men and somewhat more common for women, although still comprising only a minority; and (c) temporary negative effects were more common, reported by a minority of men and a minority to a majority of women." | ||

*'''Daly, N. R. (2021). [https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cps_stuetd | *'''Daly, N. R. (2021). [https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1135&context=cps_stuetd Relationship of Child Sexual Abuse Survivor Self-Perception of Consent to Current Functioning], PhD thesis.''' | ||

*:"In 1998 Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman conducted a meta-analysis using a college sample which challenged the prevailing belief that childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has inherent deleterious effects. Resultantly, the authors proposed alternative terminology (e.g., child-adult sex), without adequate investigation into what distinguishes child-adult sex from CSA. In response, the current study investigated the relationship between CSA, consent and adult functioning in a college sample [...] These results suggest that based on CSA status, a college sample does not exhibit significant deficits in psychological functioning or family environment and may not be comparable to samples of CSA survivors in the general population." | *:"In 1998 Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman conducted a meta-analysis using a college sample which challenged the prevailing belief that childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has inherent deleterious effects. Resultantly, the authors proposed alternative terminology (e.g., child-adult sex), without adequate investigation into what distinguishes child-adult sex from CSA. In response, the current study investigated the relationship between CSA, [[consent]] and adult functioning in a college sample [...] These results suggest that based on CSA status, a college sample does not exhibit significant deficits in psychological functioning or family environment and may not be comparable to samples of CSA survivors in the general population." | ||

*'''Lahtinen, H., et al., (2018). "[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29096161/ Children's disclosures of sexual abuse in a population-based sample]," ''Child abuse and Neglect'', Feb 2018; 76: 84-94.''' | |||

*:'''Note:''' 2.4% of the sample (12 and 15 year olds) reported CSA experiences, of which the majority found them to be positive. For the boys, the experience was often positive (71%) vs (9% negative), whereas for the girls it was less often so evaluated (26%) vs (46%) negative. The most popular reason for not disclosing the contact to an adult was considering the experience not serious enough (41%). Despite a CSA sample of 256, the authors bizarrely refused to test for statistical significance of trends. | |||

*:"The small number of answers to the question of whether a sexual incident with an adult was considered negative or positive does not enable testing statistical significance [...] Most of the children reported these incidents as positive. This highlights the potentially contradictory views of an incident from the perspective of the respondent compared to that of society and the law [...] These results, taken together with the finding that many of the children did not label their experiences as sexual abuse, indicate that more age-appropriate safety education for children and adolescents is needed to encourage disclosures to adults early enough [...] Early disclosure is crucial, both for ending the abuse and for preventing perpetrators from moving on to new victims." | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, B.]] (2020). [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1007/s10508-020-01721-y "First Sexual Intercourse in the Irish Study of Sexual Health and Relationships: Current Functioning in Relation to Age at Time of Experience and Partner Age,"] ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 50(1):289-310.''' | |||

*:"The vast majority of cases involved postpubertal heterosexual coitus. Overall, minors involved with adults were not significantly less well adjusted than adults involved with other adults on a majority of measures, effect size differences in adjustment were mostly small, and mean adjustment responses consistently indicated good rather than poor adjustment." | |||

*''' | *'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, B.]] (2022). [https://ia601505.us.archive.org/10/items/rind-2022-reactions-to-minor-older-and-minor-peer-sex-in-finnish-survey/Rind%202022%20-%20Reactions%20to%20Minor-Older%20and%20Minor-Peer%20Sex%20in%20Finnish%20survey.pdf "Reactions to Minor-Older and Minor-Peer Sex as a Function of Personal and Situational Variables in a Finnish Nationally Representative Student Sample",] ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 51, p. 961–985.''' | ||

*:" | *:"Felson et al. (2019) used a large-scale nationally representative Finnish sample of sixth and ninth graders to estimate the population prevalence of negative subjective reactions to sexual experiences between minors under age 18 and persons at least 5 years older and between minors and peer-aged partners for comparison. They then accounted for these reactions in multivariate analysis based on contextual factors. The present study argued that focusing exclusively on negative reactions short-changed a fuller scientific understanding. It analyzed the full range of reactions in the same sample, focusing on positive reactions. For reactions in retrospect, boys frequently reacted positively to minor-older sex (68%, n = 280 cases), on par with positive reactions to boy-peer sex (67%, n = 1510). Girls reacted positively to minor-older sex less often (36%, n = 1047) and to girl-peer sex half the time (48%, n = 1931). In both minor-older and minor-peer sex, rates of positive reactions were higher for boys vs. girls, adolescents vs. children, when partners were friends vs. strangers or relatives, with intercourse vs. lesser forms of sexual intimacy, with more frequent sex, and when not coerced. Boys reacted positively more often with female than male partners. In minor-older sex, partner age difference mattered for girls but not boys, and the minor’s initiating the sex (14% for girls, 46% for boys) produced equally high rates of positive reactions. Most of these factors remained significant in multivariate analysis. The frequency of positive reactions, their responsiveness to context, the similarity in reaction patterns with minor-peer sex, and the generalizability of the sample were argued to contradict the trauma view often applied to minor-older sex, holding it to be intrinsically aversive irrespective of context." | ||

*:'''Note:''' Rind's analysis also identified that boys initiated 46% of their encounters with significantly older people (recalling 82% of such experiences positively), and likewise 14% for girls (79% positive recall). For girls, rates of positive reactions increased from noncontact sex to sexual touching to sexual intercourse in both minor-peer and minor-older sex, with similar rates at each level of intimacy. For intercourse, most girls reacted positively, whether with peers (57%) or older partners (63%). On the other hand, for non-contact sex, few reacted positively, whether with peers (14%) or older partners (8%). Era-related degradation in quality of experience was also indicated, suggesting moral values were to blame for some negative subjective recall. Girls with older partners reacted more negatively (46% vs. 31%) and less positively (26% vs. 47%) in the 2008–2013 surveys than in the 1988 survey. For boys, however, no signifcant diferences occurred. | |||

*:For a fuller analysis of this paper and its findings see [[Media:Rindbasics.pdf|our primer]]. | |||

*''' | *'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, B.]] (2023). [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37286764/ Subjective Reactions to First Coitus in Relation to Participant Sex, Partner Age, and Context in a German Nationally Representative Sample of Adolescents and Young Adults.] ''Arch Sex Behav.'' Jul;52(5):2229-2247. doi: 10.1007/s10508-023-02631-5. Epub 2023 Jun 7. PMID: 37286764.''' | ||

*:" | *:"Analysis of a Finnish nationally representative student sample found that subjective reactions to first intercourse (mostly heterosexual; usually in adolescence) were highly positive for boys and mostly positive for girls, whether involved with peers or adults (Rind, 2022). The present study examined the generality of these findings by examining subjective reactions to first coitus (heterosexual intercourse) in a German nationally representative sample of young people (data collected in 2014). Most first coitus was postpubertal. Males reacted mostly positively and uncommonly negatively in similar fashion in all age pairings: boy-girl (71% positive, 13% negative); boy-woman (73% positive; 17% negative); man-woman (73% positive, 15% negative). Females' reactions were more mixed, similar in the girl-boy (48% positive; 37% negative) and woman-man (46% positive, 36% negative) groups, but less favorable in the girl-man group (32% positive, 47% negative). In logistic regressions, adjusting for other factors, rates of positive reactions were unrelated to age groups. These rates did increase, in order of importance, when participants were male, their partners were close, they expected the coitus to happen, and they affirmatively wanted it. Reaction rates were computed from the Finnish sample, restricting cases to first coitus occurring in the 2000s, and then compared to minors' reactions in the German sample. The Finns reacted more favorably, similarly in both minor-peer and minor-adult coitus, with twice the odds of reacting positively. It was argued that this discrepancy was due to cultural differences (e.g., Finnish culture is more sex-positive)." | ||

*'''Larsen, K. & Larsen, H. (2007). "[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16982501/ The prevalence of unwanted and unlawful sexual experiences reported by Danish adolescents: Results from a national youth survey in 2002]," ''Acta Paediatrica'', 2006 Oct;95(10):1270-6.''' | |||

*:'''Note:''' The youth were all aged 15. Specific data in tables revealed that 7.5% of girls and 2% of boys reported encounters with a 5+ year age gap or more - 59 and 65% respectively felt they had not been abused. | |||

*:"Multimedia computer-based self-administered questionnaires (CASI) were completed by a national representative sample of 15–16-y-olds. Child sexual abuse was defined according to the penal code and measured by questions defining specific sexual activities, the relationship between the older person and the child, and the youth's own perception of the incident. Results: Among 5829 respondents, 11% reported unlawful sexual experiences, 7% of boys and 16% of girls. Only 1% of boys and 4% of girls felt that they “definitely” or “maybe” had been sexually abused. Conclusion: A relatively high percentage of Danish adolescents have early, unlawful sexual experiences. However, young people's own perception of sexual abuse tends to differ from that of the authorities, or their tolerance of abusive incidents is high. Gender differences were found in factors predicting perception of abuse." | |||

*''' | *'''Miriam Junco, Marta Ferragut & Maria J. Blanca (2022). [https://asociacionconciencia.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/2022-Child-Sexual-Abuse-Andalucia.pdf Prevalence of Child Contact Sexual Abuse in the Spanish Region of Andalusia], ''Journal of Child Sexual Abuse''''' | ||

*: | *:'''Note:''' It appears that of the respondents affirming that they were exposed to what the author of this paper defined as "sexual abuse", over half (53%) believed that at ''no point'' in their youth were they subjected to sexual abuse. | ||

*''' | *'''Madu, S. N., & Peltzer, K. (2001). [https://sci-hub.se/10.1023/A:1002704331364 Prevalence and Patterns of Child Sexual Abuse and Victim–Perpetrator Relationship Among Secondary School Students in the Northern Province (South Africa).] Archives of Sexual Behavior, 30(3), 311–321.''' | ||

*:" | *:"Among those who answered the first question, 21 (9.3%) indicated that they perceived themselves as sexually abused as a child while 195 (90.7%) did not. Among those who perceived themselves as sexually abused as a child, 7 were males (i.e., 6.5% of the male victims) and 13 were females (i.e., 11.3% of the female victims). Among those who did not perceive themselves as sexually abused as a child, 99 were males (i.e., 91.7% of the male victims) and 97 were females (i.e., 84.4% of the female victims)." | ||

*'''Rind, Bruce ( | *'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] (1995). [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.2307/3812792 "An Analysis of Human Sexuality Textbook Coverage of the Psychological Correlates of Adult - Nonadult Sex"], ''Journal of Sex Research'', 32(3), p. 219-233''' | ||

*:" | *:"First, researchers using college samples who have investigated consequences of adult-nonadult sex have generally found either no effects on psychological adjustment attributable to this experience (e.g., Cole, 1987; Fromuth, 1986; Harter, Alexander, & Neimeyer, 1988; Hatfield, 1987; Higgins & McCabe, 1994; Hrabowy & Allgeier, 1987; Pallotta, 1991; Predieri, 1991; Silliman, 1993; Zetzer, 1990), or only a few effects out of many measures--effects that have been small in terms of effect size (e.g., Alexander & Lupfer, 1987; Bergdahl, 1982; Edwards & Alexander, 1992; Fromuth & Burkhart, 1987; Haggard & Emery, 1989; Sarbo, 1984; White & Strange, 1993). Thus, college students who have experienced sex with adults when they were younger do not, as a group, exhibit the kind of maladjustment that has been frequently reported in clinical studies (for reviews of clinical studies, see, e.g., Beitchman, Zucker, Hood, DaCosta, & Akman, 1991; Beitchman et al., 1992)." | ||

*'''Baurmann, Michael C. (1983). ''[ | *'''Baurmann, Michael C. (1983). ''[https://michaelbaurmann.info/ Sexuality, Violence and Psychological After-Effects: A Longitudinal Study of Cases of Sexual Assault which were Reported to the Police]''. In: Sessar, K., Kerner, HJ. (eds) [https://annas-archive.org/md5/e11e71b71a6847dec4b3ae2c2623fa3c Developments in Crime and Crime Control Research. Research in Criminology]. Springer, New York, NY. ([https://www.ipce.info/library_2/files/baurmann.htm Ipce backup]), ([https://web.archive.org/web/20130425190201/http://snifferdogonline.com/reports/Child%20Abuse,%20Sexuality%20and%20Violence/Sexuality_%20Violence%20and%20Psychological%20After-Effects.pdf webarchive copy of the summary chapter])''' | ||

*:"The victimological analysis was based on a 4-year questionnaire study (1969 - 1972) of virtually all sexual victims known to the police in the German state of Lower Saxony (n = 8058). [...] To recapitulate, only half of the declared victims (51.8%) of indecent assault suffered from injuries or even severe trauma. The other 48.2% had no problems in connection with the experience. In most of these cases the sexual offense was relatively superficial and harmless and/or the "victim" consented to the offense (page 459). [...] Homosexual contacts played no important statistical or criminological role in this study. On the one hand, they composed only 10-15% of the cases, and on the other, the sexual contacts were described by the victims themselves as "harmless", almost exclusively without the use of violence by the suspect (page 287), and as a result, none of the male victims questioned felt themselves to have been injured. In addition no injury could be determined in these cases with the help of test procedures." | *:"The victimological analysis was based on a 4-year questionnaire study (1969 - 1972) of virtually all sexual victims known to the police in the German state of Lower Saxony (n = 8058). [...] To recapitulate, only half of the declared victims (51.8%) of indecent assault suffered from injuries or even severe trauma. The other 48.2% had no problems in connection with the experience. In most of these cases the sexual offense was relatively superficial and harmless and/or the "victim" consented to the offense (page 459). [...] Homosexual contacts played no important statistical or criminological role in this study. On the one hand, they composed only 10-15% of the cases, and on the other, the sexual contacts were described by the victims themselves as "harmless", almost exclusively without the use of violence by the suspect (page 287), and as a result, none of the male victims questioned felt themselves to have been injured. In addition no injury could be determined in these cases with the help of test procedures." | ||

*'''Steever, E. E., Follette, V. M., & Naugle, A. E. (2001). "The correlates of male adults' perceptions of their early sexual experiences, | *'''Steever, E. E., Follette, V. M., & Naugle, A. E. (2001). [https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007852002481 "The correlates of male adults' perceptions of their early sexual experiences"], ''Journal of Traumatic Stress'', 14(1), 189–204.''' | ||

*:"Three groups of participants were assessed for this study: (1) men who report no history of childhood sexual experiences or report a history of consensual childhood and adolescent sexual experiences with peers (less than five years age difference; NSA), (2) men who do not identify themselves as survivors of childhood sexual abuse, but report a history of childhood or adolescent (before age eighteen) sexual experiences that were coercive/forced in nature, occurred with an individual at least 5 years older than the subject, or were incestuous in nature (involved an older family member), thus satisfying typical research definitions of child sexual abuse (ESE), and (3) men who report a history of childhood sexual experiences that they label as sexual abuse (CSA). [...] Analysis of variance between groups revealed that Group CSA (''M'' = .71, ''SD'' = .42) reported significantly more distress than Group NSA (''M'' = .40, ''SD'' = .36) or Group ESE did (''M'' = .46, ''SD'' = .22). [...] Consistent with our hypotheses, participants in Group CSA were twice as likely to have participated in psychotherapy as participants in Group ESE. In fact, more than half of Group CSA reported that they had sought mental health treatment. [...] Participants in Group ESE, who by standard research criteria would be classified as "abused" did not seek out mental health counseling to a statistically greater degree than participants in Group NSA. Because the participants in Group ESE did not report higher levels of psychological distress than those in Group NSA, it seems likely that these men did not seek treatment because of lack of distress." | *:"Three groups of participants were assessed for this study: (1) men who report no history of childhood sexual experiences or report a history of consensual childhood and adolescent sexual experiences with peers (less than five years age difference; NSA), (2) men who do not identify themselves as survivors of childhood sexual abuse, but report a history of childhood or adolescent (before age eighteen) sexual experiences that were coercive/forced in nature, occurred with an individual at least 5 years older than the subject, or were incestuous in nature (involved an older family member), thus satisfying typical research definitions of child sexual abuse (ESE), and (3) men who report a history of childhood sexual experiences that they label as sexual abuse (CSA). [...] Analysis of variance between groups revealed that Group CSA (''M'' = .71, ''SD'' = .42) reported significantly more distress than Group NSA (''M'' = .40, ''SD'' = .36) or Group ESE did (''M'' = .46, ''SD'' = .22). [...] Consistent with our hypotheses, participants in Group CSA were twice as likely to have participated in psychotherapy as participants in Group ESE. In fact, more than half of Group CSA reported that they had sought mental health treatment. [...] Participants in Group ESE, who by standard research criteria would be classified as "abused" did not seek out mental health counseling to a statistically greater degree than participants in Group NSA. Because the participants in Group ESE did not report higher levels of psychological distress than those in Group NSA, it seems likely that these men did not seek treatment because of lack of distress." | ||

*'''[[ | *'''[[Paul Okami|Paul Okami]]. (1991). [https://sci-hub.wf/10.1007/bf01542407 Self-reports of “positive” childhood and adolescent sexual contacts with older persons: An exploratory study], ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 20, pp. 437–457.''' | ||

* | *:"An exploratory, descriptive study of 37 male and 26 female subjects reporting childhood or adolescent intergenerational sexual contacts about which subjects maintained, at least in part, "positive" feelings is reported. An informal comparison group of 7 female victims of sexual abuse also participated. Subjects were administered a 21-page, 130-item questionnaire designed to explore and evaluate childhood functioning and development, the nature of the sexual experience, and its possible impact on adult life. Eight subjects also participated in subsequent in-depth telephone interviews. A wide range of characteristics and possible effects of the experiences were reported, suggesting that intergenerational sexual contacts may represent a continuum of experience rather than a unitary and discrete pathological phenomenon". | ||

*:"Results of this study are consistent with Haugaard and Emery's (1989) observation that persons reporting "positive" childhood or adolescent intergenerational sexual contacts appear to have had "a different experience from the others." In the present investigation, positive responders' descriptions of affect and assessment of long-term effects are in sharp contrast to those of negative responders. In place of the sense of helplessness, rage, guilt, or "numbness" that typically emerge from accounts of negative experiences, one finds in many of the positive reports - particularly as expressed in the more detailed, open-ended replies and interviews - expression of warmth, pleasure, affection, humor, and even lustiness. Positive responders did not label their experiences ''sexual abuse'', did not describe experiences that would warrant application of the term ''abuse'', if the term were used in the sense of ''maltreatment'', and generally reported no harm as a result of their experiences. In fact, they frequently claimed positive benefit." (p. 453). | |||

*'''Rind, Bruce & Tromovitch, Philip (1997). "A meta-analytic review of findings from national samples on psychological correlates of child sexual abuse, | *'''[[David Finkelhor|Finkelhor, David]] (1990). [https://sci-hub.st/10.1037/0735-7028.21.5.325 Early and long-term effects of child sexual abuse: An update], ''Professional Psychology: Research and Practice'', 21(5), pp. 325-330.''' | ||

*:'''Note:''' The studies referenced here primarily utilized clinical samples. | |||

*:"Almost every study of the impact of sexual abuse has found a substantial group of victims with little or no symptomatology. Runyon (personal communication, September 23, 1988) found one quarter to one third of the victims without symptoms on the study's major clinician-rated measure of trauma. Mannarino and Cohen (1986) found 31% to be symptom-free. Tong et al. (1987) noted 36% of the children within the normal range on the Child Behavior Checklist. Conte and Schuerman (1987), using an extensive list of symptoms that included such minor items as “fearful of abuse stimuli” or such global items as “emotional upset,” found that 21% of abused children had no symptoms whatsoever (see also Sirles, Smith, & Kusama, 1989). [...] Research shows that such asymptomatic children are more likely to have been abused for a shorter period of time, without force and violence or penetration, by someone who is not a father figure and to have gotten support from parents in the context of a relatively well-functioning family (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986)." | |||

*'''[[David Finkelhor|Finkelhor, David]] and Hines, Denise (2007). [http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV150.pdf "Statutory sex crime relationships between juveniles and adults: A review of social scientific research"], ''Aggression and Violent Behavior'', 12, 300–314.''' | |||

*:[Rind Summarizes the paper] "Hines and Finkelhor (2007) focused on voluntary sexual relations between adolescents (aged 13 and older) and adults. They argued that the adolescent-adult form should be considered separately from the child–adult form, because the evidence indicates that adolescents have a greater capacity (e.g., decision-making ability, agency) to engage in sex and choose partners. Using five studies with relevant data, they reviewed each participant-partner gender combination in terms of reactions by the adolescents to the sex and the dynamics of the relationships. Combining results from these studies for the present article, rates of positive reactions for the different gender combinations were: girl-man, 46% (n = 50); boy-man, 83% (n = 54); boy-woman, 67% (n = 191); and girl-woman, 75% (n= 4). These results revealed a gender difference, with boys reacting more positively (OR = 2.59). These results were clearly not representative of the general population, being based on select convenience and college samples, but nevertheless their review added to the literature by emphasizing conceptual distinctions between child–adult and adolescent–adult sex, alerting that positive reactions can be expected in the latter in relation to certain dynamics. In their discussion of dynamics, they identified various benefits in the overall relationship that the adolescent could receive or perceive, depending on the participant-partner gender combination, which could help account for the positive reactions to the sexual aspects that did occur." | |||

*'''Adrian Coxell et al. (1999). [https://www.bmj.com/content/318/7187/846 'Lifetime prevalence, characteristics, and associated problems of non-consensual sex in men: cross sectional survey'], ''British Medical Journal (BMJ)'', vol. 318, pp. 846–50.''' | |||

*:Summarized by Rind et al. (2001)<ref>Rind et al. (2001). The Validity and Appropriateness of Methods, Analyses, and Conclusions in Rind et al. (1998): A Rebuttal of Victimological Critique From Ondersma et al. (2001) and Dallam et al. (2001)', in ''Psychological Bulletin'', Vol. 127. No. 6. pp. 734-758.</ref>: "In a recent large-scale, non-clinical study, Coxell, King, Mezey, and Gordon (1999) examined a sample of 2,474 men aged 18 to 94 in Great Britain recruited from general medical practices. Participants were asked about CSA occurring before 16 with someone at least 5 years older. In the entire sample, 7.7% of participants [i.e. 185 people] had "consensual" CSA — the authors' term — whereas 5.3% had nonconsenting CSA. Thus, 59% of CSA was consenting." (p. 744). | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] & Tromovitch, Philip (1997). [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3813384 "A meta-analytic review of findings from national samples on psychological correlates of child sexual abuse"], ''Journal of Sex Research'', 34, 237-255.''' | |||

*:"The self-reported effects data contradict the conclusions or implications presented in previous literature reviews that harmful effects stemming from CSA are pervasive and intense in the population of persons with this experience. Baker and Duncan (1985) found that, although some respondents reported permanent harm stemming from their CSA experiences (4% of males and 13% of females), the overwhelming majority did not (96% of males and 87% of females). Severe or intense harm would be expected to linger into adulthood, but this did not occur for most respondents in this national sample, according to their self-reports, contradicting the conclusion or implication of intense harm stemming from CSA in the typical case. Meta-analyses of CSA-adjustment relations from the five national studies that reported results of adjustment measures revealed a consistent pattern: SA respondents were less well adjusted than control respondents. Importantly, however, the size of this difference (i.e., effect size) was consistently small in the case of both males and females. The unbiased effect size estimate for males and females combined was ru = .08, which indicates that CSA, assuming that it was responsible for the adjustment difference between SA and control respondents, did not produce intense problems on average." | *:"The self-reported effects data contradict the conclusions or implications presented in previous literature reviews that harmful effects stemming from CSA are pervasive and intense in the population of persons with this experience. Baker and Duncan (1985) found that, although some respondents reported permanent harm stemming from their CSA experiences (4% of males and 13% of females), the overwhelming majority did not (96% of males and 87% of females). Severe or intense harm would be expected to linger into adulthood, but this did not occur for most respondents in this national sample, according to their self-reports, contradicting the conclusion or implication of intense harm stemming from CSA in the typical case. Meta-analyses of CSA-adjustment relations from the five national studies that reported results of adjustment measures revealed a consistent pattern: SA respondents were less well adjusted than control respondents. Importantly, however, the size of this difference (i.e., effect size) was consistently small in the case of both males and females. The unbiased effect size estimate for males and females combined was ru = .08, which indicates that CSA, assuming that it was responsible for the adjustment difference between SA and control respondents, did not produce intense problems on average." | ||

== | *'''Wilson, Glenn & Cox, David (1983). ''[http://www.ipce.info/host/wilson_83/index.htm The Child-Lovers: A Study of Paedophiles in Society]''. London: Peter Owen Publishers. ([https://web.archive.org/web/20130425190214/http://snifferdogonline.com/reports/Child%20Abuse,%20Sexuality%20and%20Violence/The%20Child-Lovers%20-%20A%20Study%20of%20Paedophiles%20in%20Society.pdf webarchive copy]) | ||

*:"[N]umerous empirical attempts to demonstrate that lasting psychological harm is done to a child through sexual contact with adults (e.g. changing his sex orientation, or making him impotent) have generally failed to adduce any such evidence (e.g. Tindall, 1978; Bernard, 1979). Most researchers seem to be agreed that except in the case of physical assault against an unwilling child (tantamount to rape), no lasting harm to the sexual or social development of the child ‘victim’ can be detected (Powell and Chalkley, 1981)." | |||

*'''Halina Sklenarova et al. 2018 [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0145213417304209 Online sexual solicitation by adults and peers – Results from a population based German sample]. ''Child Abuse & Neglect''''' | |||

*:"Findings illustrated that 51.3% (n = 1148) of adolescents had experienced online sexual activity, which mostly involved peers (n = 969; 84.4%). In contrast, [...] 22.2% (n = 490) reporting online sexual interactions with adults, of which 10.4% (n = 51) were perceived as negative. The findings suggest that adolescents frequently engage in sexual interactions on the Internet with only a relatively small number perceiving such contacts as exploitative." | |||

=== Outcomes and "severity" === | |||

Much literature has suggested more negative outcomes in victims of more "severe" forms of sexual abuse, such as those involving penetration, longer duration, younger age of debut, age of partner. The observed "dose–response" relationship supports a causal interpretation: greater exposure produces a stronger effect. Nevertheless, this is highly inconsistent, the results of many studies do not confirm that. (''see more in [[Research: Association or Causation]]'') | |||

*'''Browning, C. R., & Laumann, E. O. (1997). [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273078559_Sexual_Contact_between_Children_and_Adults_A_Life_Course_Perspective Sexual Contact between Children and Adults: A Life Course Perspective.] ''American Sociological Review'', 62(4), 540. doi:10.2307/2657425''' | |||

*:"We adjudicate between two competing models of the long-term effects on women of sexual contact in childhood. The psychogenic perspective conceptualizes adult-child sexual contact as a traumatic event generating intense affect that must be resolved. Behavioral attempts to deal with the trauma of adult-child sexual contact can take opposing forms - some victims will engage in compulsive sexual behavior while others withdraw from sexual activity. The more severe the sexual contact, the more adverse the long-term effects (including sexual dysfunction and diminished well-being). From our alternative life course perspective, sexual contact with an adult during childhood provides a culturally inappropriate model of sexual behavior that increases the child's likelihood of engaging in an active and risky sexual career in adolescence and adulthood. These behaviors, in turn, create long-term adverse outcomes. Using data from the National Health and Social Life Survey, we find evidence of heightened sexual activity in the aftermath of adult-child sex (predicted by both perspectives), but we find no evidence of a tendency to avoid sexual activity (predicted by the psychogenic perspective). Moreover, we find little evidence to support the hypothesis that the severity of the sexual contact increases the likelihood of long-term adverse outcomes. In contrast, we find strong evidence that sexual trajectories account for the association between adult-child sex and adult outcomes." | |||

*:"Finally, telling evidence of the influence of sexual trajectories was revealed in our analysis of the mediating impact of intervening sexual events on long-term adverse outcomes. When we controlled for intervening sexual career variables (teenage childbirth and number of sexual partners) and intervening adverse sexual experience variables (sexually transmitted infection and forced sex) we found that the direct effect of adult-child sex disappeared in most cases. More active and riskier sexual trajectories were associated with high rates of sexual dysfunction and low well-being in adulthood" | |||

* '''Edward O. Laumann, Christopher R. Browning, Arnout van de Rijt, and Mariana Gatzeva. Sexual Contact between Children and Adults: A Life Course Perspective with a special reference to men.''' in: '''[[John Bancroft|Bancroft]], J. (Ed.) (2003). [https://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=C3F0A409AC9F1193E0BA75B847BC19E4 Sexual development in childhood]. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.''' | |||

*:"The effect of adult-child sex on measures of sexual behavior over longer periods of the life course (last five years and since age 18) indicates that these experiences heighten levels of sexual activity for men but do not result in sexual withdrawal. | |||

*:The evidence suggests that childhood sexual contact tends to result in reinforcement of sexual activity generally as well as acts and relationship characteristics specific to the early sexual event. This conclusion is supported with respect to the heightened interest on oral sex if this occurred in the early event as well as the association between same-gender sexual activity during childhood and its subsequent appeal. | |||

*:Contrary to the expectations of the psychogenic perspective, the level of event severity is not associated with long-term outcomes. | |||

*:Peer contacts were associated—at magnitudes and significance levels comparable to adult-child sexual contacts—with overall well-being and sexual adjustment during adulthood. In short, age of the partner is not associated with sexual adjustment during adulthood.[...] | |||

*:The effect of adult-child sex on adult sexual adjustment appears to be mediated by a range of intervening events in the life course." | |||

*:"The importance of marital status and the appeal of short-term sexual partnering as mechanisms linking early sexual contact with adult relationship satisfaction conform to the expectations of the life course perspective. Early sexual experience may result in the assimilation of models or scripts of sexual interaction that do not facilitate the development of stable intimate relationships." | |||

*:'''Note:''' They tested two large samples, referred to as NHSLS and CHSLS, which yielded divergent results: "For the NHSLS, men’s adult-child sex is associated with all the adult adjustment variables, while for the CHSLS, it is not associated with any of these variables. Moreover, consistent with the life course perspective, for the NHSLS, peer sexual contacts were associated with both adult overall well-being and high sexual dysfunction[...] These results also run counter to the psychogenic assumption that those who experience sexual contacts with age peers will not manifest similar adult outcomes. However, for the CHSLS no significant differences in adult well-being or sexual adjustment between men with and without peer sexual experiences were found." | |||

*:'''Note:''' For the last two studies [[Research:_Secondary_Harm#Stigma_as_a_factor|stigma as a factor]] may be of relevance. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10508-020-01860-2?error=cookies_not_supported&code=af0a3560-1e1c-45a1-bfdd-79c359fac45c Moral Incongruence] typically targets non-marital sexual activity in women and same-sex sexual activity in men. | |||

*'''Rind, B., Tromovitch, P., & Bauserman, R. (2001). The validity and appropriateness of methods, analyses, and conclusions in Rind et al. (1998): A rebuttal of victimological critique from Ondersma et al. (2001) and Dallam et al. (2001). ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 30(5), 463–499. Doi:10.1023/A:1010271214506''' | |||

*:"Clearly, meta-analyses of nonclinical samples show that both men and women with a history of CSA are slightly less well adjusted than controls. However, in our society, minors in general who have precocious sex—for example, willing peer intercourse at a young age—are also less well adjusted (e.g., Jessor, Costa, Jessor, & Donovan, 1983; Ketterlinus, Lamb, Nitz, & Elster, 1992; Resnick & Blum, 1994; D. Rosenthal, Smith, & de Visser, 1999). Early sex is nonconventional in our society, but not cross culturally (Ford & Beach, 1951), and reflects a package of emotional, behavioral, familial, and social correlates that are maladaptive according to our society's standards. Jessor et al. (1983) described this package in terms of behavior problem theory, which is composed of three systems that promote nonnormative behavior. In the personality system, proneness is represented in the motivational structure; for example, the young person places a lower value on academic achievement, is more tolerant toward deviance, and is less religious. In the environment system, proneness comes from lesser parental control, greater peer influence, and social models for problem behaviors. In the behavior system, proneness is reflected in greater involvement in other problem behaviors and simultaneous less involvement in conventional behaviors, such as doing well in school. Early sex is seen as originating in these systems rather than causing them. This point is relevant to cause and effect regarding CSA" | |||

*'''Shen, F., Liu, Y. (2023). [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370523396_Perceived_Parental_Attachment_and_Psychological_Distress_Among_Child_Sexual_Abuse_Survivors_The_Mediating_Role_of_Coping_Strategies Perceived Parental Attachment and Psychological Distress Among Child Sexual Abuse Survivors: The Mediating Role of Coping Strategies.] ''J Fam Viol''. DOI:10.1007/s10896-023-00568-w''' | |||

*:"[W]e did not find that either approach coping or avoidance coping mediated the effect of CSA severity on the psychological distress; CSA severity was not significantly associated with coping or psychological distress." | |||

*'''Maniglio, R. (2012). [https://sci-hub.st/10.1177/1524838012470032 Child Sexual Abuse in the Etiology of Anxiety Disorders. A Systematic Review of Reviews]. ''TRAUMA, VIOLENCE, & ABUSE''''' | |||

*:"Four meta-analyses, including 3,214,482 subjects from 171 studies, were analyzed." | |||

*:"There is evidence that child sexual abuse is a significant, although general and nonspecific, risk factor for anxiety disorders, especially posttraumatic stress disorder, regardless of gender of the victim and severity of abuse." | |||

*:"Of the moderators concerning aspects of the abuse experience and definition (i.e., penetration, force, frequency, and duration of abuse, relationship to the perpetrator, age when abused, and definition of child sexual abuse based on maximum age of victim, level of contact, and consent), definition of abuse including consent, abuse involving contact, and relationship to the perpetrator generated conflicting results, with some evidence suggesting greater risk of anxiety problems in college survivors of intrafamilial abuse, and, only for females in college victims of abuse including both willing and unwanted sex. All the other moderators concerning abuse characteristics generated nonsignificant results. As described in the introduction section, much literature has suggested more negative outcomes in victims of more severe and traumatic forms of sexual victimization, such as those involving force, violence, and multiple perpetrators. Nevertheless, the results of this systematic review do not confirm suspicions that such factors along with other variables concerning aspects of the victimization experience (such as younger age when abused, longer duration or higher frequency of abuse) increase anxiety symptoms or disorders in people who have been sexually victimized as children." | |||

*:“Importantly, most studies investigating the relationship between child sexual abuse and anxiety disorders have not controlled for the overlap with other traumatic events, especially co-occurring forms of maltreatment such as physical and emotive abuse. [Only Rind et al. 1998 has, and show that...] Family variables were more strongly linked with anxiety problems, especially for generic anxiety symptoms and obsessive–compulsive symptomatology, than was child sexual abuse" | |||

*'''Nagtegaal, M. H., & Boonmann, C. (2021). [https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2021.1985673 Child Sexual Abuse and Problems Reported by Survivors of CSA: A Meta-Review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse], 31(2), 147–176. This is a shortened and adapted version of a study conducted in 2012 for and at the request of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. See English summary of the [https://repository.wodc.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12832/115/cahier-2012-6-summary_tcm28-72523.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y Self-reported problems following child sexual abuse. A meta-review.]''' (Cahier 2012-6) . | |||

*:"The results showed that the attitude and reactions by people who are working in health care can sort their influence on the severity of the reported problems. Further, the number of sexual partners that someone has had, influenced adult sexual revictimization. Next, different coping styles influenced the severity of the problems, that is, coping styles that deny or suppress the CSA are related to more problems in adulthood. Finally, persons who are being treated in a clinical setting report more problems than other persons. The other circumstances/characteristics that were examined, but overall did not sort moderating influence were: the nature of CSA (CSA in general or CSA with specific characteristics), the frequency of CSA, the age at which CSA took place, the way CSA was ascertained, the relation between the perpetrator and the victim and gender. This means that problems after CSA are reported broadly by all victims of CSA." [Editor's note: this meta-review openly state its government association and concern regarding "a paedophile organization called ‘Vereniging Martijn’", thus compromising its scientific aim, also it did not evaluate cofounding variables, and in depth reading show significant inconsistency in findings on perpetrator-victim relations.] | |||

==LGBT Outcomes== | |||

Urban American LGBT males have a uniquely low mean average age of sexual debut (14.5).<ref>[Halkitis, P. N., LoSchiavo, C., Martino, R. J., De La Cruz, B. M., Stults, C. B., & Krause, K. D. (2020). [https://sci-hub.se/10.1080/00224499.2020.1783505 Age of Sexual Debut among Young Gay-identified Sexual Minority Men: The P18 Cohort Study]. The Journal of Sex Research, 1–8. doi:10.1080/00224499.2020.1783505]</ref> The average age difference for partners among such youth is around 6 years, making the age gap too great for most legal "[[Consent|close in age exemptions]]" and in violation of most definitions of "Child Sexual Abuse".<ref>[https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/sexual-risk-behaviors-of-gay-lesbian-and-bisexual-youths-in-new-y Rosario, M., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Hunter, J., & Gwadz, M. (1999). Sexual risk behaviors of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths in New York City: Prevalence and correlates. AIDS Education and Prevention, 11(6), 476-496.]</ref> | |||

Gay/Trans people have recalled positive experiences in surveys addressing early sexual encounters with an adult. This is of strategic relevance, particularly to trans people who are attacked by Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists and the Alternative Right for supposedly seeking to "normalize" adult-minor relations. If such claims of benign intergenerational and age gap relationships are being made by some gay and trans people, and [[Gays Against Groomers|opposed by others]], ''the personal experiences of LGBT people'' can be said to favor the claimant. | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] (2018): [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1007/s10508-018-1196-5 First Postpubertal Same-Sex Sex in Kinsey's General and Prison Male Same-Sex Samples: Comparative Analysis and Testing Common Assumptions in Minor-Adult Contacts]. ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', published online 5-JUN-2018. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-018-1196-5''' | |||

*:"Prison participants had a minor–adult contact as their first postpubertal same-sex sex twice as often as general participants, and their experience involved penetration in three-quarters of cases compared to only half the time for general participants, and it was paid for (i.e., prostitution) three times as often. Despite these differences, reactions to these events by prison and general participants were the same, with combined results of 66% positive reactions (i.e., enjoyed it “much”) versus 15% emotionally negative reactions (e.g., shock, disgust, guilt). [...] Comparing prison and general participants also showed that the CSA–trauma–crime link often claimed (i.e., where minor–adult sex is said to produce trauma that leads to later criminal behavior) did not hold in the Kinsey same-sex samples, because trauma (the middle element) was mostly missing. This null result for the link alerts that trauma needs to be shown rather than assumed when considering this link." | |||

*:"Examining reactions in relation to technique is useful for assessing claims about seriousness, with its assumed greater trauma, often made in reference to minor–adult sex [...] Younger boys with men reacted emotionally negatively ''less'' often with increasing levels of invasiveness in a significant linear trend: outercourse (28%), oral intercourse (16%), and anal intercourse (0%)." | |||

*:"Regarding minors with adults, participants with no arousal on seeing males still reacted positively in the majority of cases and infrequently reacted emotionally negatively." | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] (2017): [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1007/s10508-017-1025-2 First Postpubertal Male Same-Sex Sexual Experience in the National Health and Social Life Survey: Current Functioning in Relation to Age at Time of Experience and Partner Age]. ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', published online 17-JUL-2017. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-017-1025-2''' | |||

*:"Men whose first postpubertal same-sex sexual experience was as a minor with an adult were as well adjusted as controls. [...] these men were just as healthy, happy, sexually well adjusted, and successful in educational and career achievement. [...] This result is sharply at odds with the pathology perspectives, from which evidence for harm would be expected in ''any'' sample." | |||

*:"It revealed, for example, that nearly all the minor–adult experiences involved intercourse (i.e., oral or anal) as the most intense form of contact. Despite the view within the pathology perspectives that more intense or invasive forms of sex are more ‘‘severe’’ and thus pathogenic, no supporting evidence in the minor–adult group emerged. For example, the minor–adult group, with its mostly ‘‘severe’’ experiences, was just as well adjusted as minors with peers, who had far fewer such experiences." | |||

*:"The pathology perspectives do not distinguish between opposite-sex and same-sex attracted male minors in terms of how they might respond to minor–adult contacts. The current results, however, showed that same-sex attracted adolescent minors were especially receptive to these relations." | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, B.]] (2016). [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27783171/ "Reactions to First Postpubertal Female Same-Sex Sexual Experience in the Kinsey Sample: A Comparison of Minors with Peers, Minors with Adults, and Adults with Adults,"] ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 46(5):1517-1528.''' | |||

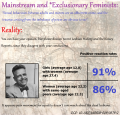

*:"Data were collected by Kinsey interviewers between 1939 and 1961 (M year = 1947). Girls under 18 (M age = 14.9), whose sexual experience was with a woman (M age = 26.3), reacted positively just as often as girls under 18 (M age = 14.1) with peers (M age = 15.0) and women (M age = 22.7) with women (M age = 26.3). The positive-reaction rates were, respectively, 85, 82, and 79 %. In a finer-graded analysis, younger adolescent girls (≤14) (M age = 12.8) with women (M age = 27.4) had a high positive-reaction rate (91 %), a rate reached by no other group. For women (M age = 22.2) with same-aged peers (M age = 22.3), this rate was 86 %." | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] and Max Welter (2016): [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1080/19317611.2016.1150379 Reactions to First Postpubertal Coitus and First Male Postpubertal Same-Sex Experience in the Kinsey Sample: Examining Assumptions in German Law Concerning Sexual Self-Determination and Age Cutoffs]. ''International Journal of Sexual Health'', published online 11-FEB-2016. DOI: 10.1080/19317611.2016.1150379''' | |||

*:”Contrary to assumptions, for example, minors ≤13 with adults reacted just as positively and no more negatively than adults with adults.” | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, B.]] (2016). [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27178172/ "Reactions to First Postpubertal Male Same-Sex Sexual Experience in the Kinsey Sample: A Comparison of Minors With Peers, Minors With Adults, and Adults With Adults,"] ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 45(7):1771-1786.''' | |||

*:"Rind and Welter (2014) examined first postpubertal coitus using the Kinsey sample, finding that reactions were just as positive, and no more negative, among minors with adults compared to minors with peers and adults with adults. In the present study, we examined first postpubertal male same-sex sexual experiences in the Kinsey same-sex sample (i.e., participants mostly with extensive postpubertal same-sex behavior), comparing reactions across the same age categories. These data were collected between 1938 and 1961 (M year: 1946). Minors under age 18 years with adults (M ages: 14.0 and 30.5, respectively) reacted positively (i.e., enjoyed the experience "much") often (70 %) and emotionally negatively (e.g., fear, disgust, shame, regret) infrequently (16 %). These rates were the same as adults with adults (M ages: 21.2 and 25.9, respectively): 68 and 16 %, respectively. Minors with peers (M ages: 13.3 and 13.8, respectively) reacted positively significantly more often (82 %) and negatively nominally less often (9 %). Minors with adults reacted positively to intercourse (oral, anal) just as often (69 %) as to outercourse (body contact, masturbation, femoral) (72 %) and reacted emotionally negatively significantly less often (9 vs. 25 %, respectively). For younger minors (≤14) with adults aged 5-19 years older, reactions were just as positive (83 %) as for minors with peers within 1 year of age (84 %) and no more emotionally negative (11 vs. 7 %, respectively). Results are discussed in relation to findings regarding first coitus in the Kinsey sample and to the cultural context particular to Kinsey's time." | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] (2013): [https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1007/s10508-013-0080-6 Homosexual Orientation - From Nature, Not Abuse: A Critique of Roberts, Glymour, and Koenen (2013)]. ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 42 (8) 1653-1664. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-013-0080-6''' | |||

*:"Roberts, Glymour, and Koenen (2013), using instrumental variable models, argued that child abuse causes homosexual orientation, defined in part as any same-sex attractions. Their instruments were various negative family environment factors. In their analyses, they found that child sexual abuse (CSA) was more strongly related to homosexual orientation than non-sexual maltreatment was, especially among males. The present commentary therefore focused on male CSA. It is argued that Roberts et al.’s ‘‘abuse model’’ is incorrect and an alternative is presented. Male homosexual behavior is common in primates and has been common in many human societies, such that an evolved human male homosexual potential, with individual variation, can be assumed. Cultural variation has been strongly influenced by cultural norms. In our society, homosexual expression is rare because it is counternormative. The‘‘counternormativity model’’offered here holds that negative family environment weakens normative controls and increases counternormative thinking and behavior, which, in combination with sufficient homosexual potential and relevant, reinforcing experiences, can produce a homosexual orientation. This is a benign or positive model (innate potential plus release and reinforcement), in contrast to Roberts et al.’s negative model (abuse plus emotional compensation or cognitive distortion). The abuse model is criticized for being based on the sexual victimological paradigm, which developed to describe the female experience in rape and incest. This poorly fits the gay male experience, as demonstrated in a brief non-clinical literature review. Validly understanding male homosexuality, it is argued, requires the broad perspective, as employed here." | |||

*'''Kronenfeld, O. and Nadan, Y. (2023). [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740923005340 “Will There Always Be this Dark Side?” Gay teenage boys’ sexual experiences with adult men.] ''Children and Youth Services Review''. Preprint.''' | |||

*:"The analysis yielded four themes: (1) dimensions of closet and risk; (2) mentoring versus exploitation; (3) dimensions of self-agency; and (4) the effects of the sexual experiences on the subsequent lives of the participants. These themes reflect complex experiences of the participants that varied between “dark” experiences to more “lightful” ones, with many different “shades” in between. [...] Our analysis portrays the complexity and ambivalence inherent in the experiences of gay adolescent boys in their sexual experiences with older men. We propose that these experiences be viewed on a spectrum with different variations, thereby contributing to the body of knowledge on the subject, which has tended to depict these experiences in a dichotomous manner as either positive or negative. The findings also shed light on several possible aspects enabling age-discrepant relationships, such as being in the closet and a need for gay men role models." | |||

*'''Dolezal, C. et al (2014). [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0145213413002603 "Childhood sexual experiences with an older partner among men who have sex with men in Buenos Aires, Argentina,"] ''Child Abuse & Neglect'', Volume 38, Issue 2, Pages 271-279.''' | |||

*:'''Note:''' Eighteen percent of the respondents reported sex before 13 with an age-gap partner, the majority of whom did not feel they were hurt by the experience and did not consider it to be childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Over two-thirds of reporters said that their older partner was a female. Only 4% of those with a female partner felt their experience was CSA compared to 44% of those who had a male partner. | |||

*'''Carballo-Diéguez, A. et al (2012). [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21484505/ "Recalled sexual experiences in childhood with older partners: a study of Brazilian men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender persons,"] ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 41(2):363-76.''' | |||

*:"For data analysis, raw scores were weighted based on participants' reported network size. Of 575 participants (85% men and 15% transgender), 32% reported childhood sexual experiences with an older partner. Mean age at first experience was 9 years, partners being, on average, 19 years old, and mostly men. Most frequent behaviors were partners exposing their genitals, mutual fondling, child masturbating partner, child performing oral sex on partner, and child being anally penetrated. Only 29% of the participants who had had such childhood sexual experiences considered it abuse; 57% reported liking, 29% being indifferent and only 14% not liking the sexual experience at the time it happened. Transgender participants were significantly more likely to report such experiences and, compared with men, had less negative feelings about the experience at the time of the interview. No significant associations were found between sexual experiences in childhood and unprotected receptive or insertive anal intercourse in adulthood." | |||

*:'''Rind, Bruce (2001). "[http://www.ipce.info/library_2/rind/rgb_disc.htm#Model Gay and Bisexual Adolescent Boys' Sexual Experiences With Men: An Empirical Examination of Psychological Correlates in a Nonclinical Sample]", ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 30(4), 345-368.''' | *'''Arreola, Sonya; Neilands, Torsten; Pollack, Lance; Paul, Jay; Catania, Joseph (2008). [https://sci-hub.se/10.1080/00224490802204431 "Childhood Sexual Experiences and Adult Health Sequelae Among Gay and Bisexual Men: Defining Childhood Sexual Abuse,"] ''Journal of Sex Research'', 45(3), pp. 246 - 252.''' | ||

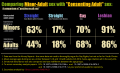

*:"Childhood sexual experience [minor-minor and adult-minor was included in this definition] was composed of three categories: None (no sex before age 18); consensual only (sex before age 18 that was NOT considered by the respondent to have been forced); and forced (having been "forced or frightened by someone into doing something sexually" at least once before age 18). [...] Interestingly, the forced sex group and the no sex group were statistically indistinguishable in their level of well-being, while the consensual sex group was significantly more likely to have a higher level of well-being than either of the other two groups. This suggests that consensual sex before 18 years of age may have a positive effect, perhaps as an adaptive milestone of adolescent sexual development. The emphasis in these data on pathology does not permit further exploration of this possibility. [...] There were no differences in rates of depression and suicidal ideation between the consensual- and no-sex groups. The consensual- and forced-sex groups had higher rates of substance use and transmission risk than the no-sex group. The forced-sex group, however, had significantly higher rates of frequent drug use and high-risk sex than the consensual group. Findings suggest that forced CSEs result in a higher-risk profile than consensual or no childhood sexual experiences, the kind of risk pattern differs between forced and consensual childhood sexual experiences, and the underlying mechanisms that maintain risk patterns may vary. It is important to clarify risk patterns and mechanisms that maintain them differentially for forced and consensual sex groups so that interventions may be tailored to the specific trajectories related to each experience." | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] (2001). "[http://www.ipce.info/library_2/rind/rind_gay_boys_frame.htm Gay and Bisexual Adolescent Boys' Sexual Experiences With Men: An Empirical Examination of Psychological Correlates in a Nonclinical Sample]", ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 30(4), 345-368''' | |||

*:"Over the last quarter century the incest model, with its image of helpless victims exploited and traumatized by powerful perpetrators, has come to dominate perceptions of virtually all forms of adult-minor sex. Thus, even willing sexual relations between gay or bisexual adolescent boys and adult men, which differ from father-daughter incest in many important ways, are generally seen by the lay public and professionals as traumatizing and psychologically injurious. This study assessed this common perception by examining a nonclinical, mostly college sample of gay and bisexual men. Of the 129 men in the study, 26 were identified as having had age-discrepant sexual relations (ADSRs) as adolescents between 12 and 17 years of age with adult males. Men with ADSR experiences were as well adjusted as controls in terms of self-esteem and having achieved a positive sexual identity. Reactions to the ADSRs were predominantly positive, and most ADSRs were willingly engaged in. Younger adolescents were just as willing and reacted at least as positively as older adolescents. Data on sexual identity development indicated that ADSRs played no role in creating same-sex sexual interests, contrary to the "seduction" hypothesis. Findings were inconsistent with the incest model. The incest model has come to act as a procrustean bed, narrowly dictating how adult-minor sexual relations quite different from incest are perceived." | |||

*'''Stanley, Jessica L., Bartholomew, Kim, and Oram, Doug (2004). "[https://web.archive.org/web/20140325145604/http://www.sfu.ca/psyc/faculty/bartholomew/faq_files/stanley1.pdf Gay and Bisexual Men's Age-Discrepant Childhood Sexual Experiences]", ''The Journal of Sex Research'', 41(4), pp. 381-389''' | |||

*:"This study examined childhood sexual abuse (CSA) in gay and bisexual men. We compared the conventional definition of CSA based on age difference with a modified definition of CSA based on perception to evaluate which definition best accounted for problems in adjustment. The sample consisted of 192 gay and bisexual men recruited from a randomly selected community sample. Men's descriptions of their CSA experiences were coded from taped interviews. Fifty men (26%) reported sexual experiences before age 17 with someone at least 5 years older, constituting CSA according to the age-based definition. Of these men, 24 (49%) perceived their sexual experiences as negative, coercive, and/or abusive and thus were categorized as perception-based CSA. Participants with perception-based CSA experiences reported higher levels of maladjustment than non-CSA participants. Participants with age-based CSA experiences who perceived their sexual experience as non-negative, noncoercive, and nonabusive were similar to non-CSA participants in their levels of adjustment. These findings suggest that a perception-based CSA definition more accurately represents harmful CSA experiences in gay and bisexual men than the conventional age-based definition. [...] no differences in adjustment were found between participants with CSE histories and participants who did not report an age-based CSA experience. Additionally, the perception-based definition predicted maladjustment in four areas of interpersonal difficulties over and above that predicted by the age-based criterion. [...] empirical evidence indicates that age-discrepant childhood sexual experiences are not necessarily harmful (e.g., Constantine, 1981; Rind et al., 1998; Steever et al., 2001). Therefore, it must be acknowledged that a violation of social norms, which is the basis for the age-based definition, does not necessarily result in harm. A definition of CSA based on social norm violations is further problematic for same-sex relations because same-sex sexual activity is considered a social norm violation by many. Some in the gay community believe that some sexual experiences involving mature adolescents and older partners may be beneficial (e.g., Sandfort, 1983; [[Ritch Savin-Williams|Savin-Williams]], 1998). Several arguments can be made supporting this position. These sexual experiences may provide these adolescents with the opportunity to explore their sexuality and feel affirmed by the gay community. Gay youth often speak of feeling different from their childhood peers and unaccepted by the dominant culture. It may be less threatening for young gay males to seekout an older gay male than to risk rejection and possible humiliation from making sexual advances toward a peer (cf. Savin-Williams, 1998). A sexual advance toward a peer may be dangerous for a gay youth if it is responded to with physical aggression, outing to the larger group of peers, and/or social rejection (Fisher & Akman, 2002). Combining perception-based CSA experience with noncoercive, nonnegative, nonabusive experiences, as the age-based definition does, presents a misleading picture of childhood sexual abuse. An age-based CSA definition inflates prevalence rates of childhood sexual abuse and inaccurately suggests that the maladjustment associated with perception-based CSA experiences applies to all childhood age-discrepant sexual encounters. In contrast, these results suggest that gay men with histories of nonnegative, noncoercive child-hood sexual experiences with older people are as well adjusted as those without histories of age-discrepant childhood sexual experiences." | |||

*'''Riegel, David (2009) [https://web.archive.org/web/20130420132331/http://snifferdogonline.com/reports/Child%20Abuse,%20Sexuality%20and%20Violence/Boyhood%20Sexual%20Experiences%20with%20Older%20Males%20-%20Using%20the%20Internet%20for%20Behavioural%20Research.pdf Boyhood Sexual Experiences with Older Males: Using the Internet for Behavioral Research.] ''Archives of sexual behavior'' DOI - 10.1007/s10508-009-9500-z''' | |||

*:“Victimology holds that all forms of boy/older male sexual contact are injurious to the younger participant (Finkelhor, 1984); therefore, ample evidence of harm should have been apparent even in this convenience sample. However, participants indicated that consent, in the ‘‘simple’’ sense, was common; enjoyment was more characteristic than displeasure or trauma; encouragement rather than resistance on their part (as the younger participant) characterized sexual interactions, especially after the first several encounters; feelings that the sexual contacts could appropriately be labeled ‘‘child sexual abuse’’ were in the minority; perceptions of shared or considerate use of power rather than being dominated in the relationships were in the majority; and self-perceived short-term and long-term effects were characteristically positive or neutral rather than negative. Finally, self-reports of current mental health indicated that most participants felt that they were emotionally healthy, coped fairly well with life’s problems, and generally had good social relations with others.” | |||

=== A note about the "Gay" label === | |||

* '''David L. Riegel (unknown year) [http://www.sexarchive.info/BIB/riegel02.htm Categorizing “Gay Teens”: A Disservice to Boys?]''' ([https://web.archive.org/web/20250130153232/http://www.sexarchive.info/BIB/riegel02.htm web.archive]) | |||

*:"young males have a common, bordering on universal, predilection to experiment with every conceivable form of potential sexual pleasure, and a significant percentage go through a stage where they want to engage to some degree in sexual explorations with other males, observations which most candid adult males would confirm from their own boyhood. But despite TEEN sexual activities too diverse to attempt to catalog, the vast majority of these experimenters, perhaps 90% or more, eventually grow up to be primarily attracted to females. | |||

*:We social scientists seem to be obsessive about categorizing people and behaviors, and compulsive about creating labels. Thus the “category/label” of “Gay Teen/Gay Youth” – and even “Gay Boy,” which presumably includes the pre-teen – has come into vogue. When invented and arbitrary “buzzwords” such as these are institutionalized and proclaimed on the Internet and other media as if they were scientifically supported truths, a boy who is simply going through a stage of TEEN sex play with other males may be unduly influenced to jump to the hasty and ill-considered conclusion that he is unalterably and permanently gay. Alternately, this Gay Teen label may be imposed by others on a boy who is discovered to have willingly participated in such TEEN activities. Such categorization is unfortunate, and makes it much more difficult for a boy to be able to choose to explore other aspects of his pansexuality." | |||

===Misuse of the "[[incest model]]"=== | |||

*'''[[Bruce Rind|Rind, Bruce]] (2001). "[http://www.ipce.info/library_2/rind/rgb_disc.htm#Model Gay and Bisexual Adolescent Boys' Sexual Experiences With Men: An Empirical Examination of Psychological Correlates in a Nonclinical Sample]", ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', 30(4), 345-368. doi: 10.1023/a:1010210630788 ''' | |||