Helmut Kentler: Difference between revisions

The Admins (talk | contribs) change titles, duplicate reference |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

<blockquote>''In 1981, Kentler was invited to the German parliament to speak about why homosexuality should be decriminalized—it didn’t happen for thirteen more years—but he strayed, unprompted, into a discussion of his experiment. “We looked after and advised these relationships very intensively,” he said. He held consultations with the foster fathers and their sons, many of whom had been so neglected that they had never learned to read or write. “These people only put up with these feeble-minded boys because they were in love with them,” he told the lawmakers.'' (from the ''New Yorker'')</blockquote> | <blockquote>''In 1981, Kentler was invited to the German parliament to speak about why homosexuality should be decriminalized—it didn’t happen for thirteen more years—but he strayed, unprompted, into a discussion of his experiment. “We looked after and advised these relationships very intensively,” he said. He held consultations with the foster fathers and their sons, many of whom had been so neglected that they had never learned to read or write. “These people only put up with these feeble-minded boys because they were in love with them,” he told the lawmakers.'' (from the ''New Yorker'')</blockquote> | ||

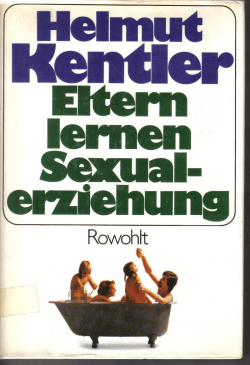

[[File:Kentlerbook.png|thumb|left|250px|Cover of Helmut Kentler’s Book Eltern Lernen Sexual-Erziehung (Parents Learn Sexual-Education), depicting parents bathing naked with their young children. Image credit: Amazon.com]] | [[File:Kentlerbook.png|thumb|left|250px|Cover of Helmut Kentler’s Book Eltern Lernen Sexual-Erziehung (Parents Learn Sexual-Education), depicting parents bathing naked with their young children. Image credit: Amazon.com]] | ||

====Intergenerational sex==== | ====Intergenerational sex==== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

===Data and findings=== | ===Data and findings=== | ||

::''[Karin] Désirat – just like Klaus Pacharzina – held similar views to Kentler on removing the taboo and decriminalizing sexual contact between adults and children. Karin Désirat interprets the two anthologies she co-edited, which contain several paedophile-friendly texts, as follows: “[...] it was also the social development on an intellectual level that finally allowed the topic of sexuality to be discussed in general. Previously, it was only discussed in quiet whispers. [...] <span style="background:#ffd9e5">At the time, it was considered revolutionary that pedophilia was being discussed openly and, in some cases, even positively.” Against this background, it can be assumed that Désirat and Pacharzina were at least not opposed to Kentler’s “experiment.”</span> (''Ibid'', p. 115).'' | {{Template:Moreinfo}}Kentler claims the results of his study to have been a "complete success."<ref>[http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/digitaz/artikel/?ressort=hi&dig=2013%2F09%2F14%2Fa0045&cHash=e431505422dca932c87867e053c44fd3 TAZ.de - Kentler's claims]</ref> Despite this, little is known about the precise data and findings of Kentler's work. This could be due to a lack of translation, possible state involvement in a cover-up, and/or loss of key documents. As to the sample size, Teresa Nentwig, a state-appointed social scientist discussed later on in this article stated “we don’t know”, explaining that city archivists blocked access to crucial data.<ref>[https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/germany-s-secret-paedophilia-experiment-1.2897942 Irish times: Nentwig's investigation]</ref> According to her investigation, “the Senate also ran foster homes or shared flats for young Berliners with pedophile men in other parts of West Germany.” Dr. Nentwig published a huge 752 page book on Kentler which hasn't been translated to English.<ref>[https://www.amazon.com/Im-Fahrwasser-Emanzipation-Irrwege-Kentler/dp/3525367635/ref=sr_1_4?crid=3NPUAJHBS8I1N&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.a8SvBE0QQWJZLQ27ynZjEyQpaPoK0OegeTLS8zJ_bLYhvNfV7H7OssYoMJ3muNj1ihUDPcm2MI8POw0gKpD5G9JyuPXS4Z87rH7212CAe7E.UXiSqNF1rJ5tePnovSvW Book on Kentler (In German)]</ref> By contrast, her 2019 report "Helmut Kentler and the University of Hannover," is publicly available for download.<ref>[https://www.uni-hannover.de/?id=8351 Dr. Teresa Nentwig, Bericht zum Forschungsprojekt: Helmut Kentler und die Universität Hannover (University of Hannover, 2019)].</ref> Nentwig argues that positive views of age-gap sexual contact were not exceptional in both the era and Left wing, progressive, radical space Kentler occupied. She writes (translated) that: | ||

::'' ''[Karin]'' Désirat – just like Klaus Pacharzina – held similar views to Kentler on removing the taboo and decriminalizing sexual contact between adults and children. Karin Désirat interprets the two anthologies she co-edited, which contain several paedophile-friendly texts, as follows: “''[...]'' it was also the social development on an intellectual level that finally allowed the topic of sexuality to be discussed in general. Previously, it was only discussed in quiet whispers. ''[...]'' <span style="background:#ffd9e5">At the time, it was considered revolutionary that pedophilia was being discussed openly and, in some cases, even positively.” Against this background, it can be assumed that Désirat and Pacharzina were at least not opposed to Kentler’s “experiment.”</span> (''Ibid'', p. 115).'' | |||

Nentwig also wrote: <span style="background:#ffd9e5">"[N]o one heard of Kentler's report at the time, or if someone did know about it, they did not see it as a problem."</span> (p. 114). | Nentwig also wrote: <span style="background:#ffd9e5">"[N]o one heard of Kentler's report at the time, or if someone did know about it, they did not see it as a problem."</span> (p. 114). | ||

A woman who worked with Kentler recalls: | A woman who worked with Kentler recalls: | ||

<blockquote>''When asked about the placement of young prostitutes [...] in foster homes with pedophiles or pederastic men, Kirsten Lehmkuhl said that she herself came from the psychoanalytically oriented residential care scene. When she applied for a job with Helmut Kentler in the early 1990s and was invited to an interview, she read Kentler's book “Surrogate Fathers. Children Need Fathers” in preparation. Lehmkuhl still remembers well how she reacted to the relevant passages in Kentler's report on the placement of young prostitutes with men who had contact with the prostitute scene: This did not seem unproblematic to her, but she recognized that here someone had actually looked at the young people as people, at their desire for closeness and security, after the boys concerned had previously experienced terrible things – in their families, in homes, at Bahnhof Zoo. Kentler made them an offer of bonding and arranged it. <span style="background:#ffd9e5">The boys could continue to live largely independently and, for example, did not have to submit to the regulations of residential care; At the same time, however, the young people’s longing for someone who liked them was fulfilled through the foster relationship. In this way, Kentler probably wanted to give them "a little bit of empowerment in a terrible situation."''</span> (p. 116).</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote>''When asked about the placement of young prostitutes ''[...]'' in foster homes with pedophiles or pederastic men, Kirsten Lehmkuhl said that she herself came from the psychoanalytically oriented residential care scene. When she applied for a job with Helmut Kentler in the early 1990s and was invited to an interview, she read Kentler's book “Surrogate Fathers. Children Need Fathers” in preparation. Lehmkuhl still remembers well how she reacted to the relevant passages in Kentler's report on the placement of young prostitutes with men who had contact with the prostitute scene: This did not seem unproblematic to her, but she recognized that here someone had actually looked at the young people as people, at their desire for closeness and security, after the boys concerned had previously experienced terrible things – in their families, in homes, at Bahnhof Zoo. Kentler made them an offer of bonding and arranged it. <span style="background:#ffd9e5">The boys could continue to live largely independently and, for example, did not have to submit to the regulations of residential care; At the same time, however, the young people’s longing for someone who liked them was fulfilled through the foster relationship. In this way, Kentler probably wanted to give them "a little bit of empowerment in a terrible situation."''</span> (p. 116).</blockquote> | |||

==Harassment== | ==Harassment== | ||

=The "Abuse of sexual abuse" | ===The "Abuse of sexual abuse" lecture scandal=== | ||

On the evening of November 6, 1993, shortly before the Kentler was set to lecture on the "Abuse of Sexual Abuse" at the Protestant Technical School for Social and Special Education in Hanover, he was on his way to the toilet when a young man - according to his retrospective account - jumped up to him with the words: "You pig, you sow, you child molester!!!" and punched him on his right cheekbone. An acquaintance immediately intervened, and it was later discovered that the attacker was a local student who had taken quotes from Kentler's books and distributed them to visitors in front of the building. Kentler, who later described the quotes as "all falsified," decided not to press charges because he was convinced that this would "hardly help" the young man, and instead suggested a meeting in what would now be labelled an example of restorative justice. This meeting took place that same year, but the young man is said to have shown little insight. | On the evening of November 6, 1993, shortly before the Kentler was set to lecture on the "Abuse of Sexual Abuse" at the Protestant Technical School for Social and Special Education in Hanover, he was on his way to the toilet when a young man - according to his retrospective account - jumped up to him with the words: "You pig, you sow, you child molester!!!" and punched him on his right cheekbone. An acquaintance immediately intervened, and it was later discovered that the attacker was a local student who had taken quotes from Kentler's books and distributed them to visitors in front of the building. Kentler, who later described the quotes as "all falsified," decided not to press charges because he was convinced that this would "hardly help" the young man, and instead suggested a meeting in what would now be labelled an example of restorative justice. This meeting took place that same year, but the young man is said to have shown little insight. | ||

Kentler wanted to give his lecture despite the attack and, according to his description, among the 200 to 250 people present were "around 20 women" who "wanted to overturn" the event. Fueled largely by the feminist magazine ''Emma'' which had condemned him around this time, Kentler suggested to these twenty or so heckling women that they select two or three of them for a panel discussion with him. They rejected this, and after one of the "wild women," as Kentler called them, addressed his friend as "you asshole," he told them: "my patience and goodwill are exhausted," leaving the event. Kentler characterized these women's actions as “against the background of a conservative, anti-sexual, anti-pleasure, anti-child attitude” that “is more rigid than anything I encountered in the 1960s and 1970s.” Kentler's failed lecture was finally published under the title "On the Abuse of Sexual Abuse" in the journal of the professional association of social workers and social educators. The groups to which his critics belonged were to receive copies; in addition, the association, which was "entirely" behind Kentler, wanted to invite them to a discussion event at the end of January 1994 at Kentler's suggestion. This event did not happen. | Kentler wanted to give his lecture despite the attack and, according to his description, among the 200 to 250 people present were "around 20 women" who "wanted to overturn" the event. Fueled largely by the [[Feminism|feminist]] magazine ''Emma'' which had condemned him around this time, Kentler suggested to these twenty or so heckling women that they select two or three of them for a panel discussion with him. They rejected this, and after one of the "wild women," as Kentler called them, addressed his friend as "you asshole," he told them: "my patience and goodwill are exhausted," leaving the event. Kentler characterized these women's actions as “against the background of a conservative, anti-sexual, anti-pleasure, anti-child attitude” that “is more rigid than anything I encountered in the 1960s and 1970s.” Kentler's failed lecture was finally published under the title "On the Abuse of Sexual Abuse" in the journal of the professional association of social workers and social educators. The groups to which his critics belonged were to receive copies; in addition, the association, which was "entirely" behind Kentler, wanted to invite them to a discussion event at the end of January 1994 at Kentler's suggestion. This event did not happen. | ||

=The University | ===The University supports its professor=== | ||

At the time, the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Hanover supported Kentler. At its meeting on 10 November 1993, four days after the incident, it passed a statement defending its member: "The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences", the statement began, notes "with dismay" that "its member Prof. Kentler, in representing his professional views as an expert on childhood sexuality, has been personally vilified, anonymously threatened and even physically attacked." The statement concludes: "The faculty stands by its colleague Prof. Kentler. It opposes behavior that destroys controversial scientific discussions by creating a hostile climate without communication." | |||

At the time, the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Hanover supported Kentler. At its meeting on 10 November 1993, four days after the incident, it passed a statement defending its member: "The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences", the statement began, notes "with dismay" that "its member Prof. Kentler, in representing his professional views as an expert on [[Research:_Youth_sexuality|childhood sexuality]], has been personally vilified, anonymously threatened and even physically attacked." The statement concludes: "The faculty stands by its colleague Prof. Kentler. It opposes behavior that destroys controversial scientific discussions by creating a hostile climate without communication." | |||

A short time later, in January 1994, the "Science-Practice Forum: Sexual Abuse - Evaluation of Practice and Research" organized by [[Katharina Rutschky]] and [[Reinhart Wolff]] took place in Berlin, which had to take place under police protection. The conference contributions were published in the same year in the anthology "Handbook of Sexual Abuse," for which Helmut Kentler wrote the essay "Perpetrators of Sexual Abuse." In February 1994, Kentler's cancelled lecture was once again the subject of the faculty meeting: It was announced that it would be repeated. "The faculty," the minutes of the relevant meeting continue, "asks Professor [Joachim] Perels to represent them at the event." This gesture - the presence of the highest-ranking representative of the faculty at the planned lecture - can be interpreted as the faculty once again supporting their colleague.<ref>The above "Harassment" section uses information freely adapted, including quotations, from an English language machine translation of Dr. Teresa Nentwig's 2019 publicly available research report on Kentler.</ref> | A short time later, in January 1994, the "Science-Practice Forum: Sexual Abuse - Evaluation of Practice and Research" organized by [[Katharina Rutschky]] and [[Reinhart Wolff]] took place in Berlin, which had to take place under police protection. The conference contributions were published in the same year in the anthology "Handbook of Sexual Abuse," for which Helmut Kentler wrote the essay "Perpetrators of Sexual Abuse." In February 1994, Kentler's cancelled lecture was once again the subject of the faculty meeting: It was announced that it would be repeated. "The faculty," the minutes of the relevant meeting continue, "asks Professor [Joachim] Perels to represent them at the event." This gesture - the presence of the highest-ranking representative of the faculty at the planned lecture - can be interpreted as the faculty once again supporting their colleague.<ref>The above "Harassment" section uses information freely adapted, including quotations, from an English language machine translation of Dr. Teresa Nentwig's 2019 publicly available research report on Kentler.</ref> | ||

| Line 50: | Line 55: | ||

Due to the journalistic work by Ursula Enders, Kentler was prevented from receiving the Magnus Hirschfeld Prize in 1997 "at the last minute". Kentler had already began the process of retiring in 1996. | Due to the journalistic work by Ursula Enders, Kentler was prevented from receiving the Magnus Hirschfeld Prize in 1997 "at the last minute". Kentler had already began the process of retiring in 1996. | ||

=In the | ===In the internet era=== | ||

Kentler's study was again publicly debated in 2015, when the Senate Youth Administration commissioned the ''political scientist'' Teresa Nentwig from the University of Göttingen to investigate it and forward her findings to the relevant authorities. Predictably, the Berlin ''Senator for Education'' Sandra Scheeres called the "experiment" at that time a "crime in state responsibility". In 2017/18, Nentwig was further commissioned in Lower Saxony to research the "effects" of Kentler's activities. Nentwig did not dismiss the possibility that Kentler himself was involved in the "abuse", despite there being no evidence or accusers. Hannover University then disowned any credit to Kentler's research after a series of politically-motivated investigations. At this point, a representative of the far-right AfD party contacted one of the participants in the study and a lawsuit against the State of Berlin was drawn up involving two former boys. According to the ''New Yorker'', for around two years, the AfD made political capital out of this at their events. On 15 June 2020, a report prepared by social scientists entitled "Helmut Kentler's Work in Berlin Child and Youth Services" was presented in Berlin. The Berlin Senator for Education Sandra Scheeres promised those effected by the "abuse" financial compensation by the State of Berlin.<ref>https://www.morgenpost.de/berlin/article229319400/Berlin-entschaedigt-Missbrauchsopfer.html</ref> The men accepted this compensation. | |||

Kentler's study was again publicly debated in 2015, when the Senate Youth Administration commissioned the ''political scientist'' Teresa Nentwig from the University of Göttingen to investigate it and forward her findings to the relevant authorities. Predictably, the Berlin ''Senator for Education'' Sandra Scheeres called the "experiment" at that time a "crime in state responsibility". In 2017/18, Nentwig was further commissioned in Lower Saxony to research the "effects" of Kentler's activities. Nentwig did not dismiss the possibility that Kentler himself was involved in the "abuse", despite there being no evidence or accusers. Hannover University then disowned any credit to Kentler's research after a series of politically-motivated investigations. At this point, a representative of the far-right AfD party contacted one of the participants in the study and a lawsuit against the State of Berlin was drawn up involving two former boys. According to the ''New Yorker'', for around two years, the AfD made political capital out of this at their events. On 15 June 2020, a report prepared by social scientists entitled "Helmut Kentler's Work in Berlin Child and Youth Services" was presented in Berlin. The Berlin Senator for Education Sandra Scheeres promised those effected by the "abuse" financial compensation by the State of Berlin.<ref name="morgen">[https://www.morgenpost.de/berlin/article229319400/Berlin-entschaedigt-Missbrauchsopfer.html Berlin Morning Post: Berlin entschädigt Missbrauchsopfer]</ref> The men accepted this compensation. | |||

==Praise== | ==Praise== | ||

=University staff who worked under Kentler= | ===University staff who worked under Kentler=== | ||

*Martin Kipp "stressed that Kentler had "a productive relationship with mistakes" from which students and staff benefited, and that he "constantly stimulated and encouraged his staff, but never put them down."<ref>Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), pp. 121-122.)</ref> | *Martin Kipp "stressed that Kentler had "a productive relationship with mistakes" from which students and staff benefited, and that he "constantly stimulated and encouraged his staff, but never put them down."<ref>Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), pp. 121-122.)</ref> | ||

*"Peter Eckardt also stressed that Kentler was never an authoritarian superior"<ref | *"Peter Eckardt also stressed that Kentler was never an authoritarian superior"<ref name="morgen" /> | ||

*"Karin Désirat repeatedly stressed the support she had received from Kentler. [...H]e had also got her her first job at the chair [...] She also owes her membership in the DGfS and the Society for the Promotion of Social Scientific Sexual Research (GFSS) to Kentler: he brought her into contact with both sexological organizations. As early as 1978, Désirat – the second woman since the founding of the DGfS in 1950 – even became a member of its board, alongside the well-known sex researchers [[Volkmar Sigusch]], [[Eberhard Schorsch]], [[Martin Dannecker]]".<ref | *"Karin Désirat repeatedly stressed the support she had received from Kentler. [...H]e had also got her her first job at the chair [...] She also owes her membership in the DGfS and the Society for the Promotion of Social Scientific Sexual Research (GFSS) to Kentler: he brought her into contact with both sexological organizations. As early as 1978, Désirat – the second woman since the founding of the DGfS in 1950 – even became a member of its board, alongside the well-known sex researchers [[Volkmar Sigusch]], [[Eberhard Schorsch]], [[Martin Dannecker]]".<ref name="morgen" /> | ||

=Praise | |||

===Praise elsewhere=== | |||

*Jan Feddersen praised Kentler in an obituary in the Tageszeitung of 12 July 2008, as a "meritorious fighter for a permissive sexual morality"<ref>http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/digitaz/artikel/?ressort=tz&dig=2008/07/12/a0152</ref> | *Jan Feddersen praised Kentler in an obituary in the Tageszeitung of 12 July 2008, as a "meritorious fighter for a permissive sexual morality"<ref>http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/digitaz/artikel/?ressort=tz&dig=2008/07/12/a0152</ref> | ||

*"Friedrich Johannsen, Dean of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Hanover from 2005 to 2009, emphasized in his memorial speech after Kentler's death: "His concept of youth work aimed at the autonomy of people and a better society."<ref>Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), p. 117.</ref> | *"Friedrich Johannsen, Dean of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Hanover from 2005 to 2009, emphasized in his memorial speech after Kentler's death: "His concept of youth work aimed at the autonomy of people and a better society."<ref>Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), p. 117.</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 22:55, 4 September 2024

Helmut Kentler (2 July 1928 in Cologne – 9 July 2008 in Hannover) was a German Psychologist, sex education expert, court-appointed specialist and professor of social education at the University of Hannover. Kentler pursued an Emancipationist Philosophy with regards to youth, but among his greatest and most contentious achievements was his work with the disadvantaged, particularly delinquent male youth and their carers. From 1979 to 1982 he was president of the German Society for Social-Scientific Sexual Research, later he was on the advisory board of the Humanistische Union. He was also a member of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sexualforschung.

Kentler was for a period, a high-profile courtroom expert in the "Squealer Assassin" mold of American defense experts Ralph Underwager and Elizabeth Loftus. Indeed, in 1999, he had planned an (as yet) unpublished book on this topic, in which he details 35 cases in which he believed strongly that the accused were innocent.[1]

Since his death, Kentler's work has been defamed in a campaign of posthumous and political/opportunistic systemic legacy harassment. A number of highly sensational media hit pieces, laden with emotionalism and capitalized upon by right wing (AfD) political interests have ensued. Two men have since testified against Kentler after receiving legal aid from the party, and were handsomely compensated by the State of Berlin as a result.[2]

Emancipatory ideology

For Helmut Kentler, theory and practice were tightly knit throughout his life. He developed a theory of emancipatory youth work via his work with adolescents and young adults as a student, and the five years he spent working in church educational institutions. He implemented group pedagogy and team work, as trusting and respectful cooperation between educators with different professional competence, and attempted to gain insight into the psychological and social connection between learning and emancipation. During the student riots in Berlin, Kentler was temporarily active as a "psychological consultant for police issues".[3] The sexual liberation movement of Berlin students in communities and shared flats, resulted in his advocacy of an emancipatory sexual education in the home,[4]. Advocating for sex education to be taught in the home was not uncommon in the 1970s,[5] and this ideological trend was reflected in his dissertation in 1975, which earned him credence as an expert in sex education for the rest of his professional life. Kentler also occasionally makes reference to influential sexual liberation theorists of the time, such as Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse.[6]

View of pederasty

[...] I have [...] in the vast majority of cases made the experience that pederastic conditions can have a very positive effect on the personality development of a boy, especially if the pederast is a real mentor of the boy. (Helmut Kentler, 1999)

In 1981, Kentler was invited to the German parliament to speak about why homosexuality should be decriminalized—it didn’t happen for thirteen more years—but he strayed, unprompted, into a discussion of his experiment. “We looked after and advised these relationships very intensively,” he said. He held consultations with the foster fathers and their sons, many of whom had been so neglected that they had never learned to read or write. “These people only put up with these feeble-minded boys because they were in love with them,” he told the lawmakers. (from the New Yorker)

Intergenerational sex

In Kentler's view, it was not enough for parents to avoid putting obstacles in the way of their children's sexual desires; rather, parents should introduce their children to sexuality, because otherwise they "risk leaving them sexually underdeveloped, becoming sexual cripples".[7] Early experiences of coitus are useful, because teenagers with coitus experience "demand an independent world of teenagers and more often reject the norms of adults".[8] Kentler warned the parents against being concerned over rape or molestation of children by adults: "The wrong thing to do now would be for parents to lose their nerve, panic and run straight to the police. If the adult had been considerate and tender, the child could even have enjoyed sexual contact with him".[9] "If such relationships are not discriminated against by the environment, then the more the older one feels responsible for the younger one, the more positive consequences for personality development can be expected", he wrote in 1974 in his foreword to the controversial sex education book, Zeig mal![10] (En: "Show Me!", documented in full at BoyWiki.[11])

Some sources such as the New Yorker claim that Kentler disowned his views on intergenerational sex in the early 90s following the suicide of an adoptive son he was said to have claimed was abused by his birth mother. It was unclear to what extent this would have been political (at the time, moral panic was at its highest in Germany), but his 1999 opinion on pederasty above appears to conflict with this, as does Rudiger Lautmann's obituary.[1] The worst of the harassment against his legacy took place long after his withdrawal from the debate on intergenerational sexuality, and death.

Famous study

At the end of the 1960s, in a model experiment, he placed several delinquent 13 to 15-year-old boys, whom he considered "secondary mental defectives", with pederasts he knew - in order to contribute towards their socialization as productive adults. These studies (whose scale is unknown) were conducted in Berlin with the support of the Youth Welfare Office. Kentler did not hide the fact that he placed young people with pederasts he knew. He reported about it in his book Leihväter from 1989. He also maintained contacts with the former participants during his teaching activities in Hanover and, in an expert opinion for the Berlin Family Court in the early 1990s, recommended that one of the youths continue to stay with his pederastic foster father, whom he described as a pedagogical natural talent.[12]

Data and findings

Call for input!

|

Kentler claims the results of his study to have been a "complete success."[13] Despite this, little is known about the precise data and findings of Kentler's work. This could be due to a lack of translation, possible state involvement in a cover-up, and/or loss of key documents. As to the sample size, Teresa Nentwig, a state-appointed social scientist discussed later on in this article stated “we don’t know”, explaining that city archivists blocked access to crucial data.[14] According to her investigation, “the Senate also ran foster homes or shared flats for young Berliners with pedophile men in other parts of West Germany.” Dr. Nentwig published a huge 752 page book on Kentler which hasn't been translated to English.[15] By contrast, her 2019 report "Helmut Kentler and the University of Hannover," is publicly available for download.[16] Nentwig argues that positive views of age-gap sexual contact were not exceptional in both the era and Left wing, progressive, radical space Kentler occupied. She writes (translated) that:

- [Karin] Désirat – just like Klaus Pacharzina – held similar views to Kentler on removing the taboo and decriminalizing sexual contact between adults and children. Karin Désirat interprets the two anthologies she co-edited, which contain several paedophile-friendly texts, as follows: “[...] it was also the social development on an intellectual level that finally allowed the topic of sexuality to be discussed in general. Previously, it was only discussed in quiet whispers. [...] At the time, it was considered revolutionary that pedophilia was being discussed openly and, in some cases, even positively.” Against this background, it can be assumed that Désirat and Pacharzina were at least not opposed to Kentler’s “experiment.” (Ibid, p. 115).

Nentwig also wrote: "[N]o one heard of Kentler's report at the time, or if someone did know about it, they did not see it as a problem." (p. 114).

A woman who worked with Kentler recalls:

When asked about the placement of young prostitutes [...] in foster homes with pedophiles or pederastic men, Kirsten Lehmkuhl said that she herself came from the psychoanalytically oriented residential care scene. When she applied for a job with Helmut Kentler in the early 1990s and was invited to an interview, she read Kentler's book “Surrogate Fathers. Children Need Fathers” in preparation. Lehmkuhl still remembers well how she reacted to the relevant passages in Kentler's report on the placement of young prostitutes with men who had contact with the prostitute scene: This did not seem unproblematic to her, but she recognized that here someone had actually looked at the young people as people, at their desire for closeness and security, after the boys concerned had previously experienced terrible things – in their families, in homes, at Bahnhof Zoo. Kentler made them an offer of bonding and arranged it. The boys could continue to live largely independently and, for example, did not have to submit to the regulations of residential care; At the same time, however, the young people’s longing for someone who liked them was fulfilled through the foster relationship. In this way, Kentler probably wanted to give them "a little bit of empowerment in a terrible situation." (p. 116).

Harassment

The "Abuse of sexual abuse" lecture scandal

On the evening of November 6, 1993, shortly before the Kentler was set to lecture on the "Abuse of Sexual Abuse" at the Protestant Technical School for Social and Special Education in Hanover, he was on his way to the toilet when a young man - according to his retrospective account - jumped up to him with the words: "You pig, you sow, you child molester!!!" and punched him on his right cheekbone. An acquaintance immediately intervened, and it was later discovered that the attacker was a local student who had taken quotes from Kentler's books and distributed them to visitors in front of the building. Kentler, who later described the quotes as "all falsified," decided not to press charges because he was convinced that this would "hardly help" the young man, and instead suggested a meeting in what would now be labelled an example of restorative justice. This meeting took place that same year, but the young man is said to have shown little insight.

Kentler wanted to give his lecture despite the attack and, according to his description, among the 200 to 250 people present were "around 20 women" who "wanted to overturn" the event. Fueled largely by the feminist magazine Emma which had condemned him around this time, Kentler suggested to these twenty or so heckling women that they select two or three of them for a panel discussion with him. They rejected this, and after one of the "wild women," as Kentler called them, addressed his friend as "you asshole," he told them: "my patience and goodwill are exhausted," leaving the event. Kentler characterized these women's actions as “against the background of a conservative, anti-sexual, anti-pleasure, anti-child attitude” that “is more rigid than anything I encountered in the 1960s and 1970s.” Kentler's failed lecture was finally published under the title "On the Abuse of Sexual Abuse" in the journal of the professional association of social workers and social educators. The groups to which his critics belonged were to receive copies; in addition, the association, which was "entirely" behind Kentler, wanted to invite them to a discussion event at the end of January 1994 at Kentler's suggestion. This event did not happen.

The University supports its professor

At the time, the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Hanover supported Kentler. At its meeting on 10 November 1993, four days after the incident, it passed a statement defending its member: "The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences", the statement began, notes "with dismay" that "its member Prof. Kentler, in representing his professional views as an expert on childhood sexuality, has been personally vilified, anonymously threatened and even physically attacked." The statement concludes: "The faculty stands by its colleague Prof. Kentler. It opposes behavior that destroys controversial scientific discussions by creating a hostile climate without communication."

A short time later, in January 1994, the "Science-Practice Forum: Sexual Abuse - Evaluation of Practice and Research" organized by Katharina Rutschky and Reinhart Wolff took place in Berlin, which had to take place under police protection. The conference contributions were published in the same year in the anthology "Handbook of Sexual Abuse," for which Helmut Kentler wrote the essay "Perpetrators of Sexual Abuse." In February 1994, Kentler's cancelled lecture was once again the subject of the faculty meeting: It was announced that it would be repeated. "The faculty," the minutes of the relevant meeting continue, "asks Professor [Joachim] Perels to represent them at the event." This gesture - the presence of the highest-ranking representative of the faculty at the planned lecture - can be interpreted as the faculty once again supporting their colleague.[17]

Due to the journalistic work by Ursula Enders, Kentler was prevented from receiving the Magnus Hirschfeld Prize in 1997 "at the last minute". Kentler had already began the process of retiring in 1996.

In the internet era

Kentler's study was again publicly debated in 2015, when the Senate Youth Administration commissioned the political scientist Teresa Nentwig from the University of Göttingen to investigate it and forward her findings to the relevant authorities. Predictably, the Berlin Senator for Education Sandra Scheeres called the "experiment" at that time a "crime in state responsibility". In 2017/18, Nentwig was further commissioned in Lower Saxony to research the "effects" of Kentler's activities. Nentwig did not dismiss the possibility that Kentler himself was involved in the "abuse", despite there being no evidence or accusers. Hannover University then disowned any credit to Kentler's research after a series of politically-motivated investigations. At this point, a representative of the far-right AfD party contacted one of the participants in the study and a lawsuit against the State of Berlin was drawn up involving two former boys. According to the New Yorker, for around two years, the AfD made political capital out of this at their events. On 15 June 2020, a report prepared by social scientists entitled "Helmut Kentler's Work in Berlin Child and Youth Services" was presented in Berlin. The Berlin Senator for Education Sandra Scheeres promised those effected by the "abuse" financial compensation by the State of Berlin.[18] The men accepted this compensation.

Praise

University staff who worked under Kentler

- Martin Kipp "stressed that Kentler had "a productive relationship with mistakes" from which students and staff benefited, and that he "constantly stimulated and encouraged his staff, but never put them down."[19]

- "Peter Eckardt also stressed that Kentler was never an authoritarian superior"[18]

- "Karin Désirat repeatedly stressed the support she had received from Kentler. [...H]e had also got her her first job at the chair [...] She also owes her membership in the DGfS and the Society for the Promotion of Social Scientific Sexual Research (GFSS) to Kentler: he brought her into contact with both sexological organizations. As early as 1978, Désirat – the second woman since the founding of the DGfS in 1950 – even became a member of its board, alongside the well-known sex researchers Volkmar Sigusch, Eberhard Schorsch, Martin Dannecker".[18]

Praise elsewhere

- Jan Feddersen praised Kentler in an obituary in the Tageszeitung of 12 July 2008, as a "meritorious fighter for a permissive sexual morality"[20]

- "Friedrich Johannsen, Dean of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Hanover from 2005 to 2009, emphasized in his memorial speech after Kentler's death: "His concept of youth work aimed at the autonomy of people and a better society."[21]

- Some protestant church authorities expressed a similar opinion. In an obituary, the Study Centre for Protestant Youth Work pointed out Kentler's controversial positions, but also acknowledged his work for "institutional structure and professional socialisation" and the attempts to make homosexuality socially acceptable in the church.

- The Humanist Union pays positive tribute to Kentler's person and body of work. In his obituary it says: "A lighthouse of our advisory board has gone out. Like no other, Helmut Kentler embodied the humanistic task of an enlightened sex education, and he was also a role model for public science. (...) His habitus combined the qualities of competence, authenticity and closeness in a rare way, with which Kentler impressed his readers and listeners alike ... Since he immediately aroused sympathies, many have confided in him."[1]

- In 2008, the (German) Journal for Sexual Research, the organ of the DGfS, published an obituary for Helmut Kentler that resembled a eulogy. On six pages, Rudiger Lautmann and the sociologist Elisabeth Tuider praise him as one of the "significant figures in sexual science in the last third of the 20th century."[22]

See also

External links

- American Conservative - Full New Yorker article currently behind paywall, but copied here and archive.

- Wikipedia

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Rudiger Lautmann - Obit for Humanistische Union

- ↑ Teller Report: Compensation Award

- ↑ Spiegel - Feind im Innern

- ↑ Parents learn sexual education, Rowohlt, 1975

- ↑ For example, see Dr. William A. Block, For Kids Only: Illustrated Family Sex Album (Trenton, N.J.: Prep Publications, 1979). Described as "Dr. Block's do-it-yourself Illustrated Human Sexuality Book for Kids"(!)

- ↑ Herbert MARCUSE: Liberation of Sexuality. In: Helmut Kentler (ed.): Sexualwesen Mensch. Texte zur Erforschung der Sexualitat (Munich: Piper 1988) pp. 222-233; Show Me! discusses Reich.

- ↑ "Parents learn sexual education", S. 32

- ↑ H. Kentler: "Sex education". 1970, p. 179

- ↑ Parents learn sexual education, pp. 103 f.

- ↑ Zeig mal! Wuppertal 1974, foreword

- ↑ BoyWiki: Show Me!, including foreword by Helmut Kentler

- ↑ http://www.haz.de/Hannover/Aus-der-Stadt/Uebersicht/Hannover-Sexualwissenschaftler-Helmut-Kentler-bringt-Pflegekinder-bei-Paedophilen-unter

- ↑ TAZ.de - Kentler's claims

- ↑ Irish times: Nentwig's investigation

- ↑ Book on Kentler (In German)

- ↑ Dr. Teresa Nentwig, Bericht zum Forschungsprojekt: Helmut Kentler und die Universität Hannover (University of Hannover, 2019).

- ↑ The above "Harassment" section uses information freely adapted, including quotations, from an English language machine translation of Dr. Teresa Nentwig's 2019 publicly available research report on Kentler.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Berlin Morning Post: Berlin entschädigt Missbrauchsopfer

- ↑ Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), pp. 121-122.)

- ↑ http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/digitaz/artikel/?ressort=tz&dig=2008/07/12/a0152

- ↑ Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), p. 117.

- ↑ Dr. Teresa Nentwig 2019 report (translated), p. 150.

- Official Encyclopedia

- Censorship

- Sociological Theory

- Hysteria

- Religion

- Youth

- Research

- Research into effects on Children

- People

- People: German

- People: Deceased

- People: Academics

- Law/Crime

- Law/Crime: German

- History & Events: German

- History & Events: 1960s

- History & Events: 1970s

- History & Events: 1980s

- History & Events: 1990s

- History & Events: 2010s

- History & Events: Real Crime

- History & Events: Personal Scandals

- Research: Children's Sexuality

- History & Events: Moral controversies